What really hides inside that spoonful of golden cloudberry sauce on a Christmas dessert? According to a new genomic study, quite a lot. Researchers in Norway have built a detailed DNA map of the cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus) and found that this much-loved Arctic berry carries eight copies of its genome with roots in several different parent species.

A holiday berry with a long human history

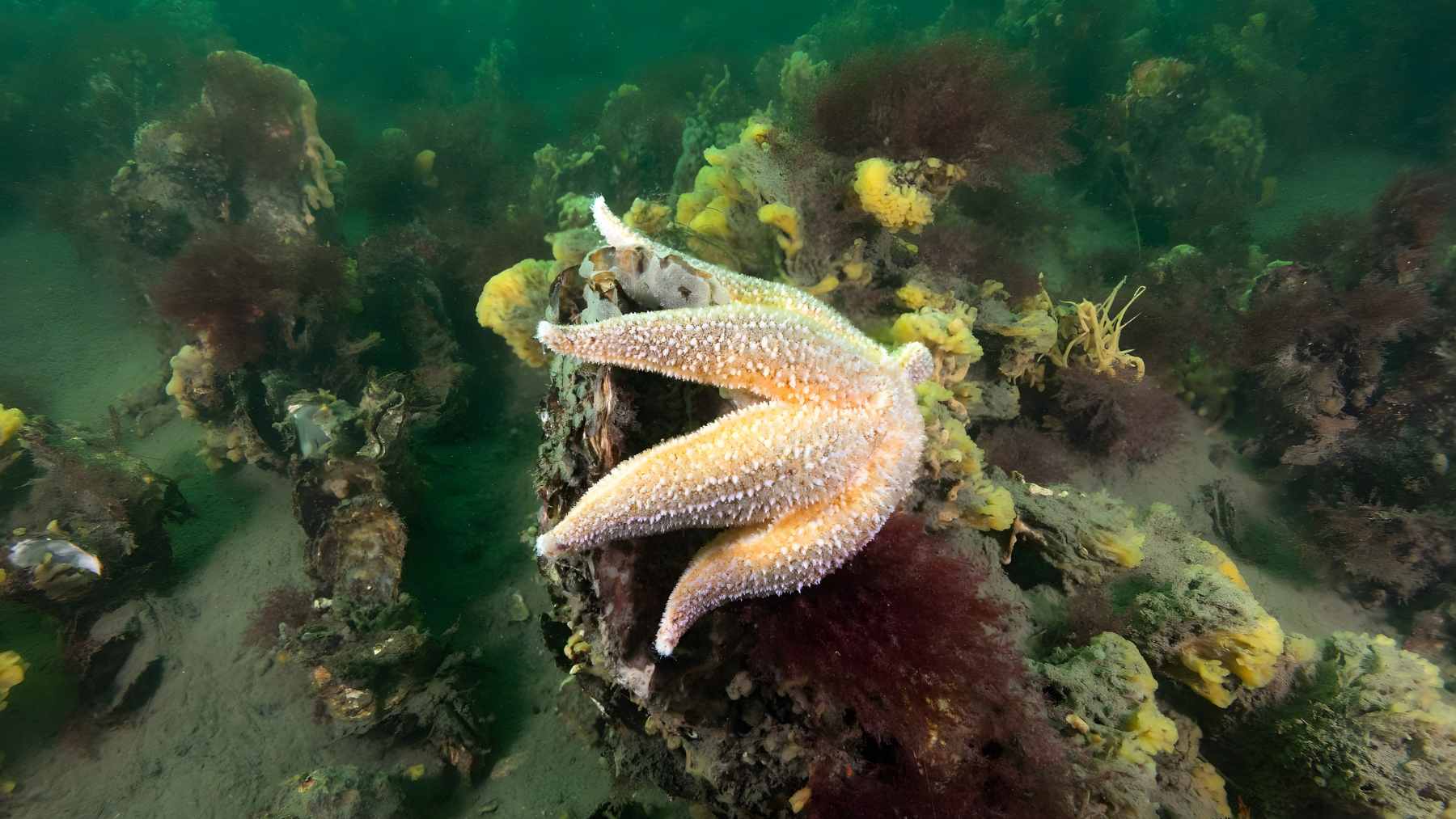

Cloudberries grow in cool peatlands and tundra across the northern hemisphere. They are especially common in Nordic bogs, where people have picked them for centuries despite wet boots, mosquitoes and unpredictable harvests.

The berries are packed with vitamin C and other antioxidants. Historical sources suggest that Vikings and later Arctic explorers used them to ward off scurvy, and nutrition historian Kaare R. Norum notes that Fridtjof Nansen loaded his Fram expedition with large stores of cloudberries as insurance against the disease.

Today they still show up on dinner tables as jam, sauce or liqueur. They are also notoriously hard to cultivate, which is one reason a small jar can feel more expensive than it looks.

A moonshot for biology reaches a Nordic bog

The new genome is part of the Earth BioGenome Project, an international effort that aims to sequence, catalog and analyze the genomes of all known eukaryotic species within about ten years.

Its organizers describe it as a moonshot for biology that should support biodiversity conservation, agriculture and a more sustainable bioeconomy.

Norway contributes through Earth BioGenome Project Norway, which focuses on species that matter for local ecosystems and society.

Cloudberry easily qualifies. It is both a cultural icon and a key player in boreal peatlands, habitats that store huge amounts of carbon yet are increasingly stressed by drainage and climate change.

Eight chromosome copies and many ancestors

Unlike humans, which carry two sets of chromosomes, cloudberries are octoploid. Each cell carries eight genome copies. That kind of multiplication is common in plants but it can make genome assembly extremely tricky because long stretches of DNA look almost identical.

To avoid sequencing a rare outlier, Norwegian scientists chose a typical male plant from a bog near Ås. The plant was moved into a simple planter box, then leaf samples were taken and sequenced using high-end long-read technology.

Despite the expected challenges, the team reports that the different chromosome copies turned out to be more distinct than feared, which made it easier to stitch the genetic “book” back together.

The deeper surprise came when they compared those eight copies. Only two chromosome sets clearly stood apart, suggesting that the cloudberry genome formed through several rounds of hybridization and genome doubling rather than a single event.

Analyses point toward contributions from both American and Eurasian relatives in the Rubus genus, although the exact parents remain uncertain because many candidate species do not yet have complete genomes of their own.

Why a berry genome matters for climate and conservation

At first glance this might sound like trivia for plant geneticists. In practice, a high-quality reference genome can help researchers track how cloudberry populations respond to warming temperatures, shifting water tables and peatland drainage. Peatlands cover only a few percent of Earth’s land surface yet store more carbon than all forests combined, and their vegetation is already changing as the climate warms.

Genomic tools also open the door to more targeted breeding. Over time, scientists may be able to study traits linked to berry yield, disease resistance or flowering time, which could eventually make small-scale cloudberry cultivation more reliable and reduce pressure on wild bogs.

By the Earth BioGenome Project’s own framing, digital DNA libraries like this are meant to support both conservation and sustainable use of species that people depend on.

So the next time a spoonful of cloudberry sauce lands on your plate, it carries a new story. Not only about holiday traditions and Arctic history but also about a complex genome that is now part of a global effort to understand and protect life on a changing planet.

The study was published on BioRxiv.