Every human cell is supposed to carry forty six chromosomes. When an embryo has one extra or one missing, the result is aneuploidy. Many such embryos never implant or fail in the first weeks, before a period is even late. Among miscarriages that doctors do detect in the first or second trimester, about half are linked to these chromosome count errors.

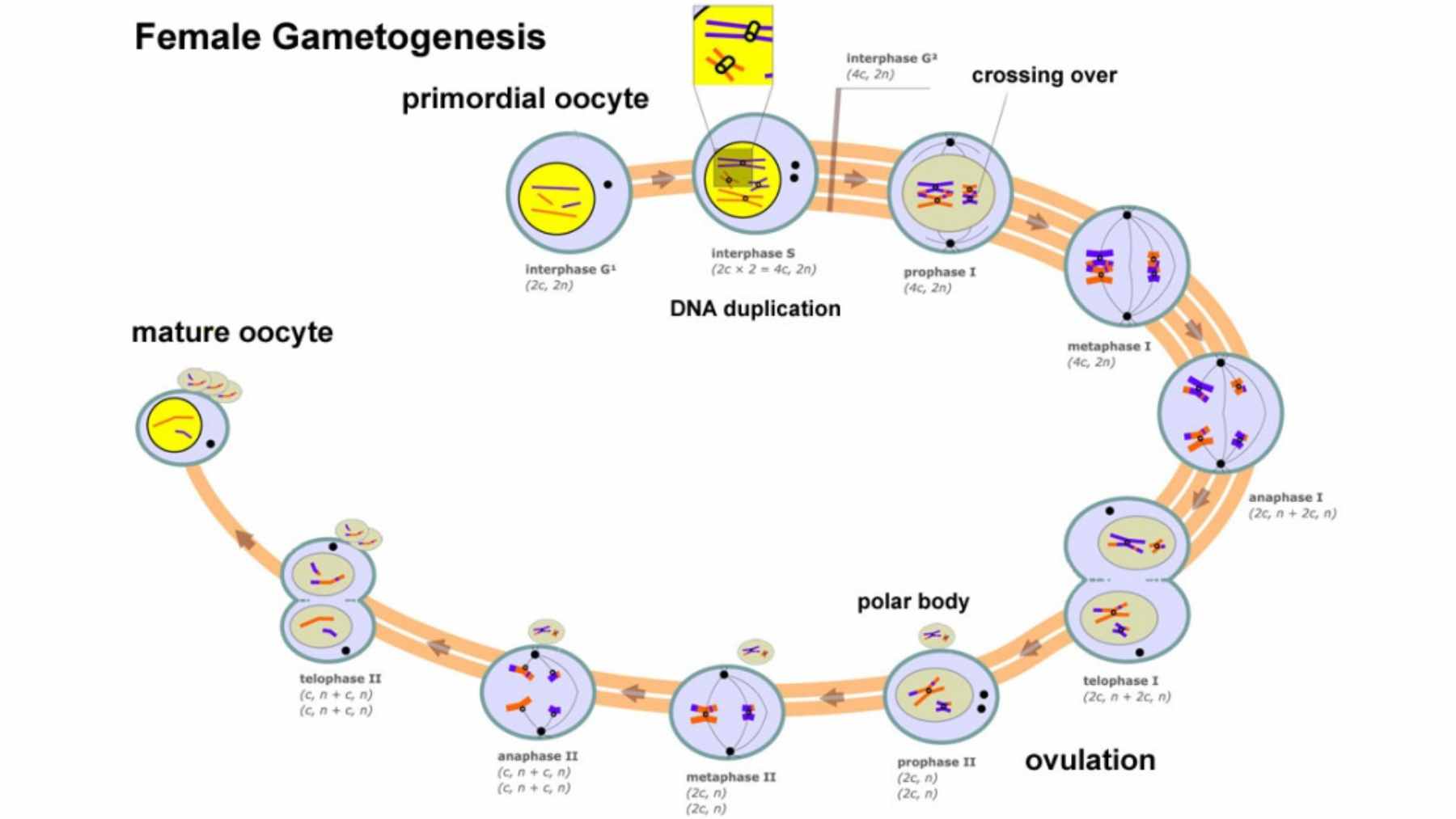

Most of the time, the problem begins in the egg. To create eggs and sperm, the body uses a special type of cell division called meiosis.

The process carefully shuffles DNA and then halves the chromosome number, so that when egg and sperm meet, the total adds back up correctly. It sounds neat and tidy. In reality, it is a high-wire act.

For people with ovaries, meiosis begins before birth. Chromosomes pair and swap pieces of DNA during fetal development, then everything pauses for years. Only later in life does the process resume for ovulation and possible fertilization.

That long pause is one reason aneuploidy becomes more common as women age, since the molecular “glue” that holds chromosomes together can weaken over time.

So when does the risk really begin? The new study suggests the answer is “much earlier than you might think.”

A massive look inside IVF embryos

To dig into that question, a team led by Rajiv McCoy at Johns Hopkins University turned to data from in vitro fertilization clinics. They analyzed preimplantation genetic testing results from 139,416 IVF embryos created by 22,850 sets of biological parents.

That huge data set allowed them to track more than 3.8 million crossover events, the DNA swaps that help align chromosomes, and identify 92,485 aneuploid chromosomes in 41,480 embryos.

When the team compared embryos with normal chromosomes to those with errors, a clear pattern appeared. Embryos with aneuploidy tended to have fewer crossovers. In plain language, the chromosomes had not paired and exchanged DNA as often as they should, which made missteps during separation more likely.

That was the first clue that common genetic differences affecting recombination might quietly influence miscarriage risk.

Genes that hold everything together

The researchers then looked for genetic variants in parents that were linked to both crossover patterns and aneuploidy in their embryos. The strongest signal came from a region that includes the SMC1B gene, which helps form ring shaped structures that hold chromosomes together during meiosis.

A particular version of this gene was associated with fewer crossovers and a higher chance of maternal meiotic aneuploidy.

Other genes popped up as well, including C14orf39, CCNB1IP1, and RNF212. All of them play roles in how chromosomes pair up and exchange DNA. Experimental work in mice and worms had already pointed to these genes as key players.

The new results show that, in humans, common variants in the same genes are tied to whether an embryo ends up with the correct chromosome count.

In effect, small inherited differences in the machinery that organizes chromosomes can tilt the odds. Not enough to dictate anyone’s fate, but enough to matter when you look across many thousands of embryos.

What it means for families right now

If you have lived through miscarriage or fertility treatment, you might wonder what this means for you. The researchers and outside experts are careful to say that these findings do not yet allow doctors to predict an individual’s risk with precision.

Each common genetic variant has a tiny effect compared with bigger drivers such as maternal age and environmental exposures.

There is another important nuance. The data come from people undergoing IVF with genetic testing, not from the general population. That introduces some bias, since couples in fertility clinics often differ in age, medical history, or reproductive challenges compared with those who conceive without assistance.

Still, the work offers a new map of the molecular pathways that can lead to pregnancy loss. In practical terms, that means researchers can now focus on a short list of genes and processes when they design future studies, drug targets, or improved risk models that use IVF testing data.

For couples sitting in a waiting room at a fertility clinic, it may eventually translate into more tailored counseling about why embryos are not implanting and what options exist.

At the end of the day, the study underscores a sobering idea with a hopeful twist. The roots of many miscarriages lie in fragile events that unfold before a woman is born, yet understanding those events is the first step toward new ways to protect future pregnancies.

The study was published in Nature.