If you’ve ever tried to judge a neighborhood by looking at just one street, you know how misleading that can be. Astronomers have a similar problem. We can see stars and glowing gas, but most of the mass around our galaxy is invisible.

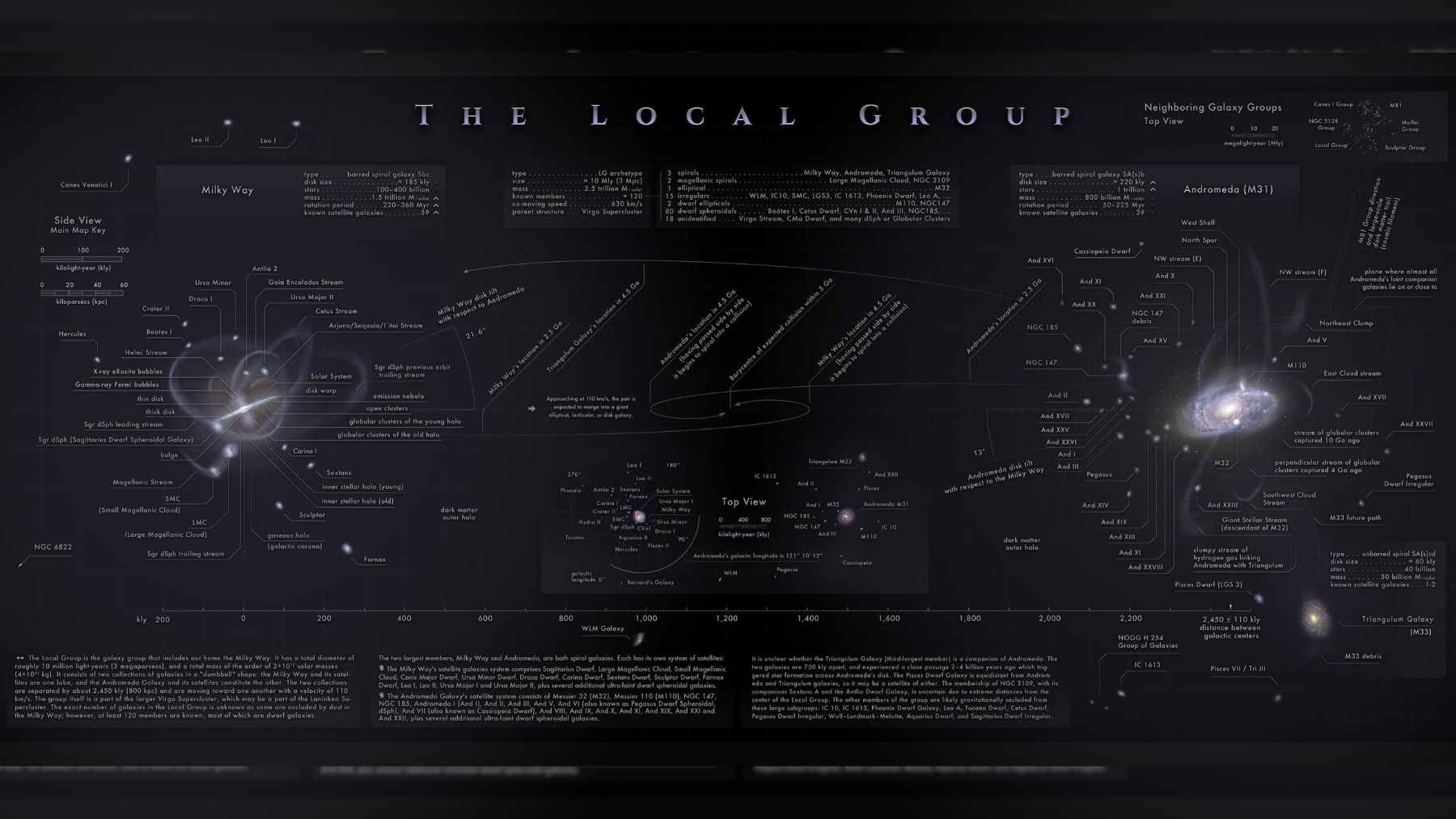

Now, a new study argues that the Milky Way is not sitting inside a roughly “round” cloud of matter, as many simplified models assume. Instead, it appears to be embedded in a vast, flattened “sheet” dominated by dark matter that stretches tens of millions of light-years and is bordered above and below by comparatively empty regions.

That geometry matters because it helps solve an old, stubborn puzzle about our local cosmos. And it does so without breaking the standard picture of how the universe evolves.

A long-standing cosmic mismatch

For almost a century, scientists have known that the universe is expanding, with galaxies generally moving away faster the farther out they are. But there’s a famous exception close to home.

The Andromeda galaxy is approaching the Milky Way at about 100 kilometers per second, even as many other nearby galaxies keep drifting away in a relatively calm local expansion. Why does our nearest big neighbor rush toward us while the broader neighborhood seems oddly “quiet”?

Past models often treated the mass around the Local Group (the Milky Way, Andromeda, and their companions) as if it were arranged more or less spherically. That approach looks tidy on paper.

The trouble is, it has struggled to reproduce the observed “cold” local Hubble flow, meaning the small deviations from smooth expansion. In the Nature Astronomy paper, the authors show that a spherical infall model fails badly compared with the motions in their constrained simulations.

The new idea is flat, not round

So what changes if the mass is arranged like a sheet? In a truly spherical system, the gravitational pull at a given distance mainly depends on the mass enclosed inside that radius. But a strongly-flattened structure behaves differently.

The study explains that mass located farther out within the same plane can tug outward in a way that partially offsets the inward pull you might expect from the Local Group itself. In plain terms, gravity still wins, but it pulls in a more complicated pattern when matter is spread out like a pancake rather than a ball.

The team’s simulations infer a sheet-like mass distribution extending out to at least 10 megaparsecs, which is about 33 million light-years. Above and below that plane are deep underdense regions, essentially local voids.

They also quantify what “sheet-like” means. The azimuthally averaged density on the midplane is about twice the cosmic mean. The “central overdensity spike” has a thickness of about 1.64 megaparsecs, or roughly 5 million light-years, based on how long the smoothed density stays above the cosmic average.

The void-like regions above and below the plane drop to roughly a quarter to a third of the mean density.

How do you weigh invisible matter?

Because dark matter does not emit light, the team had to infer it through motion. They used a Bayesian reconstruction framework called BORG (short for Bayesian Origin Reconstruction from Galaxies) to generate many realistic “Local Group analogues” inside a Lambda CDM universe. Then they boosted the resolution using 169 Gadget-4 resimulations.

The constraints were not vague. Their setup required halos forming at the observed positions of the Milky Way and Andromeda with consistent masses and relative motion, and it also required matching the recession speeds at the locations of 31 nearby isolated galaxies out to about 4 megaparsecs.

One key result is that the simulated peculiar velocities are small where we have most of our local “tracer” galaxies. Within the sheet region where most tracers lie, the mass-weighted random motions are only about 22 kilometers per second (as a one-dimensional root mean square).

That’s a very “cold” flow. Yet the same simulations predict strong anisotropy, with much larger inflow speeds toward the poles of the sheet, in areas where we have far fewer nearby galaxies to measure.

Why it matters beyond astronomy circles

It’s tempting to treat this as a purely academic detail, something that lives in journal pages and supercomputer clusters. But mapping the local mass distribution is like calibrating the “terrain” under every nearby-galaxy measurement.

When astronomers use local galaxy motions to test cosmology, the invisible matter around us is the hidden slope that can speed things up or slow them down. Getting that terrain right reduces the risk of misreading what the data are actually saying.

The work also points to a straightforward next check. The authors note that finding more isolated galaxies at high “supergalactic latitude” closer than about 5 megaparsecs could provide a decisive test, because the biggest predicted inflows occur where our current tracer sample is thin.

In other words, the universe may not be playing favorites with the Milky Way. We might just be sitting in a flat part of the cosmic landscape.

The study was published in Nature Astronomy.