If you have ever tiptoed across a rocky beach and worried about stepping on a sea urchin, you probably did not imagine you were dodging a brain. New research suggests that the purple sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus is exactly that, a spiky ball whose entire body acts like one giant brain. The finding is forcing scientists to rethink what intelligent life can look like in the ocean and beyond.

An international team led by biologists Periklis Paganos and Jack Ullrich-Lüter at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples has mapped the cell types in young sea urchins and found a surprisingly complex nervous system woven through the whole animal.

Instead of a simple nerve net, they uncovered what the team describes as an “all-body brain”, filled with neurons that use many of the same genes and chemical messengers found in vertebrate brains. For a creature that looks like a golf ball covered in spikes, that is quite a plot twist.

A spiky ball with a hidden nervous system

Paracentrotus lividus is a small, purple sea urchin that lives on rocky seafloors in the Mediterranean and along parts of the Atlantic coast, where it grazes on algae and hides in crevices. To most divers and beachgoers it is just another prickly hazard, a simple animal that sticks to rocks and minds its own business.

For decades, textbooks described sea urchins and their echinoderm relatives as having only a basic ring of nerves and radial cords, not a real brain at all.

That picture was based on anatomy you can see with a microscope, not on a full inventory of the animal’s cells and genes. Earlier genetic studies already hinted that sea urchins use some of the same molecular tools as more complex animals, but they did not show how those tools were organized in the adult body. The new work takes that step and reveals a nervous system that is anything but primitive.

How the “all-body brain” was discovered

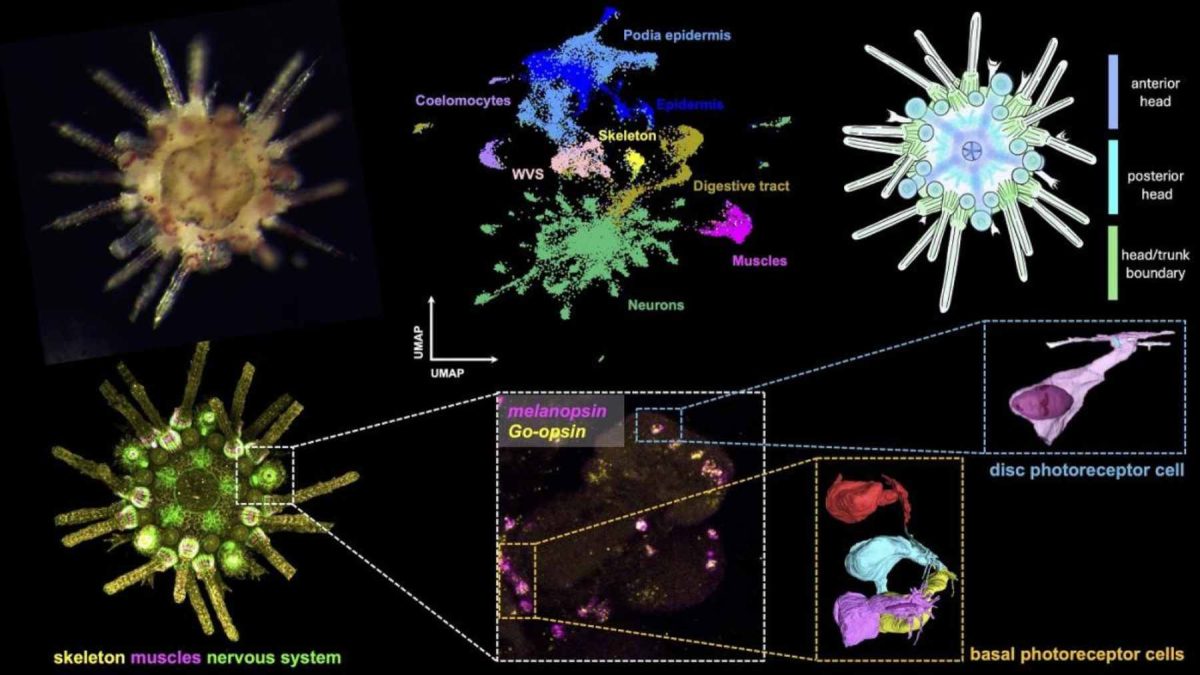

The research team used a technique known as single nucleus transcriptomics, which reads which genes are active in thousands of individual cells. By combining that with detailed staining of tissues in young, post-metamorphic sea urchins, they built a cell atlas that groups cells by type and function.

In practical terms, it is like taking a crowded stadium, tagging every person, and then sorting them into families, jobs, and neighborhoods.

More than half of the cell clusters in this atlas turned out to be neurons, an enormous share for such a small creature. Within those clusters the team identified hundreds of distinct neuronal cell types that use a rich mix of chemical messengers, including dopamine and serotonin, the same molecules that help carry signals in human brains. That diversity alone suggests a nervous system built for fine-tuned control, not just simple reflexes.

The genetic patterns were just as striking. Genes that in other animals help build the head and brain were active all across the sea urchin’s surface, while genes linked to trunk structures were mostly restricted to internal organs such as the gut and water vascular system.

“Our results show that animals without a conventional central nervous system can still develop a brain like organization,” explained Ullrich-Lüter, who says this finding changes how researchers think about nervous system evolution.

Seeing the world without a head

The scientists also found many light-sensitive cells scattered across the sea urchin’s skin and tube feet, a bit like having tiny eyes built into every patch of surface. These photoreceptor cells carry opsins, proteins that respond to light and are also found in the human retina. Although the animal has no visible eyes, this distributed setup likely lets it detect light and shadow from all directions.

Imagine walking through your day with your entire skin acting as one big light sensor. For a sea urchin, that could mean knowing when a predator swims overhead or when a rock offers better shade on a bright afternoon. Large parts of its nervous system seem to respond to light, hinting that behavior such as movement and feeding may be tuned by subtle shifts in brightness on the seafloor.

Other research from the same Italian institute has followed specific hormone-producing neurons through sea urchin development, showing how their networks grow denser and more interconnected as the animal matures.

Taken together, these studies paint a picture of a creature that is quietly sensing and responding to its environment in far more sophisticated ways than a casual glance would suggest. It is not a brain in the way we experience one, but it is not a simple bundle of wires either.

Rethinking what counts as intelligence

When people talk about intelligence, they usually picture a single brain tucked inside a skull and packed with neurons. Sea urchins upend that image by showing that a highly organized nervous system can be spread across an entire body and still coordinate complex behavior.

Every move of a spine or tube foot seems to be part of a broader conversation taking place along this body wide network.

To be clear, no one claims that a purple sea urchin is solving math problems on the ocean floor. Researchers say its intelligence is more about flexible responses to the environment, like adjusting posture and grip as currents shift or food appears.

That kind of adaptability still matters if you are trying to survive in a crowded rocky neighborhood full of waves, fish, and other urchins.

The study also pushes scientists to compare this “all-body brain” with other unusual nervous systems in nature, from octopus arms that can act semi-independently to starfish that navigate using a ring of nerves.

For the most part, all of these animals rely on a similar genetic toolkit, yet they arrange their neurons in very different ways. Experts argue that understanding those differences is key if we want a fuller picture of how intelligence evolves on Earth and maybe on other worlds too.

Why this tiny animal matters for brain research

Sea urchins are distant relatives of vertebrates, which makes them a valuable comparison point for understanding how our own brains came to be. By tracing which genes are shared between the urchin’s all-body nervous system and the vertebrate central nervous system, scientists can test ideas about when certain brain features first appeared in evolution.

At the end of the day, the goal is not just to catalog weird animals, but to see the bigger story that links them to us.

There are also hints that this knowledge could inspire new approaches in regenerative medicine or soft robotics, where engineers dream of machines that can sense and react along their entire surface.

If an animal with no real head can grow an integrated network that controls thousands of tiny moving parts, that is a powerful proof of concept. The next generation of bio inspired designs may borrow more from these spiky “brains” than from familiar lab animals.

And there is still plenty left to discover, especially in the deep sea where most species remain unknown and many body plans defy our expectations. Each new dive or genetic survey could reveal another creature that handles information in a way we have never imagined.

The main study was published in the journal Science Advances.