A backpack-sized ocean robot spent eight months under Antarctic ice and delivered the first continuous underwater survey of a hidden ice shelf cavity.

Drifting beneath the Denman and Shackleton ice shelves, the robot traced 190 miles of under-ice ocean for scientists tracking Antarctic change. The record is the first set of ocean measurements taken beneath an East Antarctic ice shelf, exposing where warm water meets the ice.

What the robot found matters beyond the Antarctic coast, because the stability of ice shelves will influence how fast sea levels rise worldwide.

The unlikely journey of a tiny float

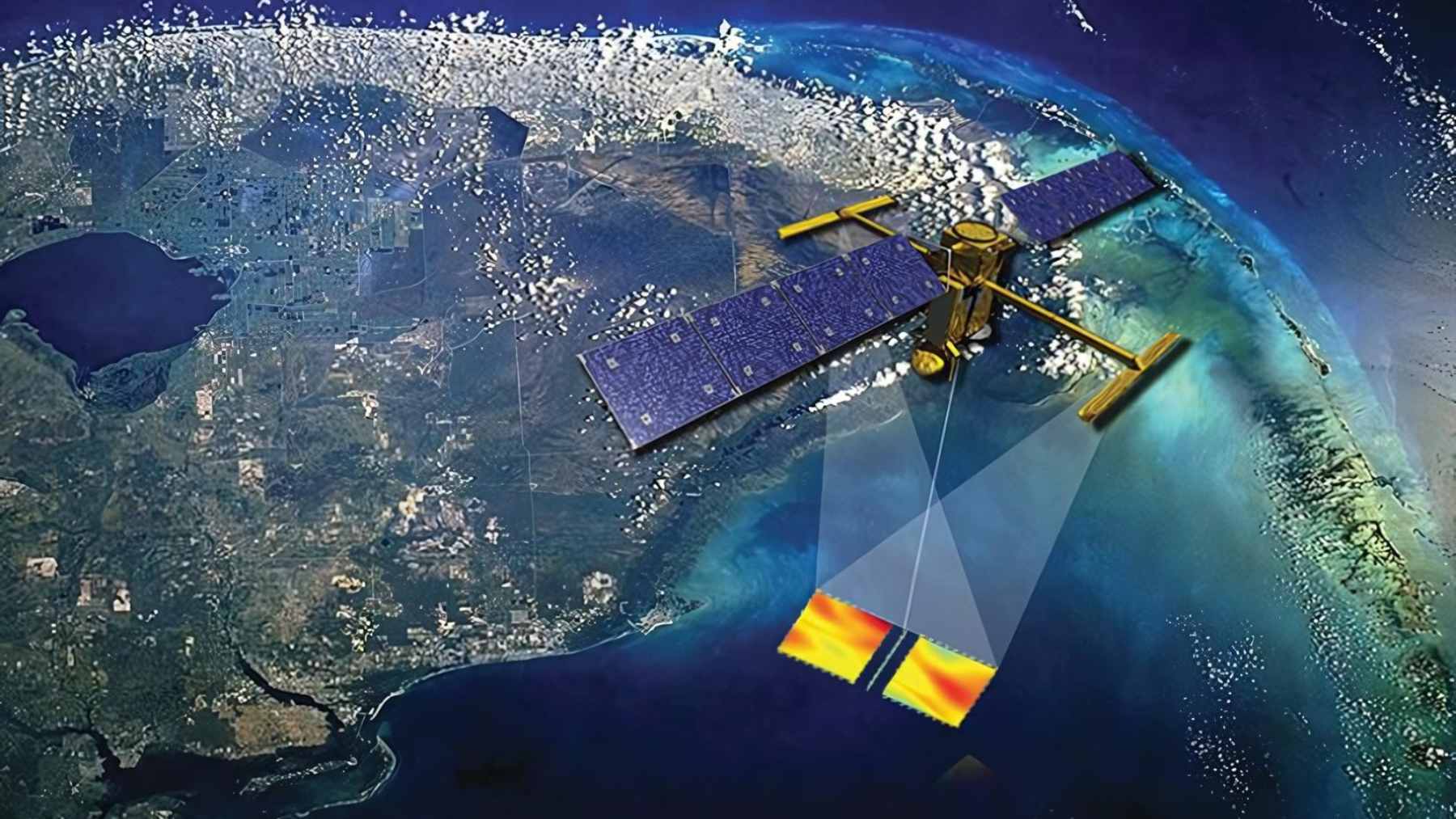

Researchers released a bright yellow Argo float, a free-drifting robot that profiles the water column, off East Antarctica.

Currents carried the float south from its launch point, then pulled it beneath the Denman and Shackleton ice shelves where satellite contact stopped. This study was led by Steve R. Rintoul, an oceanographer at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

His research focuses on how the Southern Ocean transports heat and carbon, reshaping ice shelves and global sea levels.

“These unprecedented observations provide new insights into the vulnerability of the ice shelves,” said Dr. Rintoul.

Why East Antarctic ice shelves matter

An ice shelf, a slab of floating ice, forms where a glacier flows off the continent and floats on the ocean. The shelves provide mechanical resistance, slowing the glaciers behind them, so thinning or collapse lets more land ice slide into the sea.

New work shows East Antarctica contains marine-based ice, ice resting on land below sea level and vulnerable to ocean warming.

One study found that Denman Glacier holds enough ice to raise sea levels five feet if it were lost completely.

Hidden cavities beneath Denman and Shackleton

A recent paper presents the most complete measurements yet from a single float under an East Antarctic ice shelf.

During the passage, the float measured temperature and salinity from seafloor to ice base at five-day intervals, producing 195 profiles along its track. Profiles showed Circumpolar Deep Water, a deep current around Antarctica, reaching the cavity under Denman Glacier, but waters under Shackleton stay near freezing.

This means the Denman ice shelf is exposed to ocean heat from below, while the Shackleton ice shelf sits in colder water.

Denman Glacier’s delicate balance with warm water

Earlier research using another profiling float showed that warm water, just above freezing, reaches deep channels beneath the Denman ice tongue.

When water enters the cavity, it drives basal melt, melting on the underside of the ice and thinning the shelf so ice flows faster.

“However, the Denman Glacier, with its potential 1.5-metre contribution to global sea level rise, is delicately poised,” said Dr. Rintoul. If a thicker layer of warm water pushed higher into the cavity, the added heat could trigger stronger melting along Denman’s under-ice canyon.

Shackleton ice shelf’s cooler waters for now

By contrast, the Shackleton ice-shelf cavity appears to be a cold environment where water temperatures hover close to the freezing point.

Float measurements show that water under Shackleton lacks the warm layer found under Denman, leaving the ice shelf’s base unexposed to ocean melting.

The float detected deep channels in the seafloor beneath Shackleton, features that might funnel warmer currents toward the ice shelf if circulation changes.

Now, that combination of cold water and topography leaves Shackleton less exposed than Denman, and maps of channels suggest protection might not last.

The thin boundary layers that control melting

At the ice shelf base sits the boundary layer, the thin layer of ocean water touching the ice that sets the melt rate.

Under Denman, the float found a fresh layered boundary layer that limits mixing, so warming can take longer to reach the ice base. Under parts of Shackleton, the boundary layer looks thicker and less stratified, implying that currents can mix heat upward when warm water arrives.

Because models often assume a well-mixed boundary layer, these observations will help scientists update how they represent heat transfer from ocean to ice.

Robot floats join the Antarctic observing network

Compared with research ships or drills through ice, autonomous floats can wander into places that are risky or expensive for crews.

Thousands of such instruments roam the ocean, and this expedition shows that with careful programming, some can work for months beneath ice shelves. Rintoul expects the measurements to tighten how models handle ocean-ice interactions, reducing uncertainty in sea level projections that planners rely on.

A success like this makes it easier for agencies to back more experimental floats, building a year-round network along the Antarctic continental shelf.

What this tiny float achieved

By vanishing under ice and later reappearing, the float delivered the first map of ocean conditions across an East Antarctic ice shelf cavity.

That path revealed warm water reaching into Denman’s cavity while Shackleton’s remained cold, letting scientists compare two ice shelves under distinct ocean conditions. Along the way, the float measured seafloor depths that revealed ridges and trenches, replacing a view of the Shackleton system with a map.

Most importantly, the journey showed that an instrument can survive stretches under thick Antarctic ice and still return data that guide future research.

A glimpse of the future under Antarctic ice

The team leading the mission hopes to seed parts of East Antarctica with similar floats, making under-ice measurements part of the observing system.

Robot missions will not answer every question, yet each trip under the ice replaces a blank patch on the Antarctic map with numbers. For the scientists, watching the float surface again was a relief, because the instrument could have been crushed under moving ice.

As robots continue to travel beneath Antarctic ice and return, they will turn uncertainty about glaciers into numbers that help society prepare.

The study is published in Science Advances.