Scientists detected the largest black hole collision yet, producing a new black hole about 225 times the Sun’s mass.

Two US detectors in Washington and Louisiana sensed the ripple at nearly the same moment, while partner observatories overseas helped verify that the signal came from deep space and not local noise.

A signal arrives

Researchers call the signal gravitational waves, tiny ripples in space and time, that race outward when huge masses accelerate.

The work was led by Prof. Mark Hannam at Cardiff University, where his group studies black-hole mergers and waveform tools. For physicists, the finding poses a serious challenge to current ideas about how black holes form.

What made the ripple

In this event, named GW231123, two black holes spiraled together, lost energy to waves, and finally joined into one remnant.

The clearest part is the ringdown, final vibrations after a merger settles, and it can reveal the newborn black hole’s spin.

Because the system was so massive, the detectors mainly caught the last few cycles, lasting only about 0.1 second.

Numbers from the trace

The signal appeared in both detectors at the same time, allowing scientists to rule out a local disturbance.

The collaboration estimated the two objects at about 137 and 103 solar masses, far heavier than typical stellar-collapse black holes.

From their redshift, light stretched by the expanding universe, the team inferred a distance of roughly 2-13 billion light-years.

A forbidden mass range

Most black holes form when very massive stars exhaust fuel, collapse, and leave behind an event horizon, boundary where even light cannot escape.

Models predict a gap around 60-130 solar masses because some stars hit pair instability, photons form electron pairs and pressure drops, then explode completely.

At least one of the merging black holes likely sat in that gap, which makes a simple single-star origin hard.

Spins near the limit

The analysis suggests both objects had dimensionless spin, rotation speed scaled to the maximum allowed, close to the limit set by Einstein.

High spin changes the waveform shape, and it can hide details such as the orbit angle and the true mass ratio. “This event pushes our instrumentation and data-analysis capabilities to the edge of what’s currently possible,” says Sophie Bini, collaboration member.

Why modeling is hard

To decode the signal, teams compared the data with numerical relativity, computer simulations of Einstein’s equations, plus faster approximate waveform models. For this signal strength compared with background detector noise, was about 22, which is high.

Even so, different models disagreed on key details, which left the mass and spin estimates less certain than usual.

The short ringdown

A separate ringdown-only analysis checked whether the late-time signal matched a single black hole, independent of earlier cycles.

That kind of check connects to the no-hair theorem, black holes are fully described by mass and spin, in general relativity. The paper reports the remnant properties remain broadly consistent across checks, even when some full-signal models disagree about details.

Where could they grow

One idea is hierarchical mergers, where black holes grow through repeated collisions that can push their masses beyond limits set by single-star collapse.

Dense star clusters may hold black holes long enough for multiple pairings, although strong merger kicks can still eject remnants from these environments.

Repeated mergers also tend to spin up the survivors, which fits the unusually rapid rotation inferred for both objects in this system.

Clusters and kicks

Mergers can give the remnant a recoil, a shove from uneven wave emission, which matters in crowded environments.

For this merger, the inferred kick could reach around 600 miles per second, fast enough to escape some galaxies. That detail favors places with deep gravity wells, where multiple generations of black holes can stay bound and merge again.

Disks around giants

Another possibility involves an active galactic nucleus, a galaxy core feeding a supermassive black hole, with a dense gas disk.

Gas can help black holes gain mass and settle into the same plane, yet the spins may not line up neatly. Researchers say it will likely take years of work to fully untangle the signal and understand all of its implications.

A new mass class

A remnant this heavy sits among intermediate-mass black holes, black holes between stellar and supermassive sizes, which have been hard to confirm.

Before this, the heaviest confident merger, called GW190521, produced a black hole of roughly 140 solar masses. Finding more of these objects may clarify how supermassive black holes grew early, even before large galaxies fully formed.

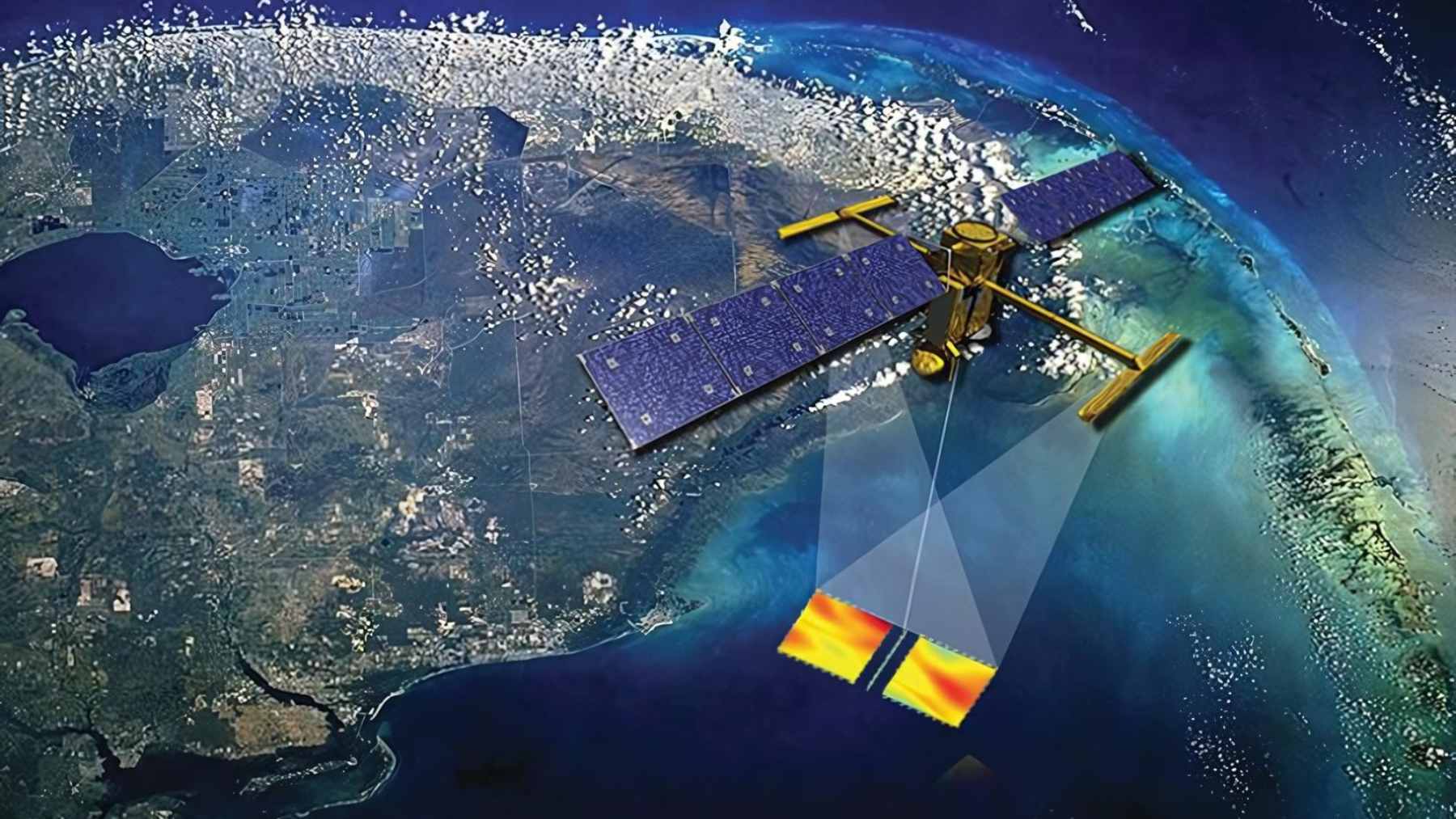

A decade of listening

LIGO, a US pair of laser observatories, first measured waves from a black hole merger, opening a new way to study the universe beyond light.

Each LIGO detector is an interferometer, a laser tool that compares path lengths, with 2.5-mile vacuum arms.

The network now pairs LIGO with Virgo in Italy and the Kamioka Gravitational Wave Detector in Japan, reducing false alarms.

Data for everyone

The team posted plots and analysis files so other researchers can rerun checks and test alternatives.

Shared strain, the fractional stretching measured by the detectors, lets independent groups hunt for glitches or missed physics. Open data also means mistakes get caught faster, and catalogs of about 300 mergers help scientists test formation ideas.

Bigger ears ahead

Next-generation gravitational-wave observatories are planned with longer arms and improved isolation, aiming to hear heavier and farther mergers.

Better low-frequency sensitivity should extend the early inspiral, giving more cycles and clearer clues about spins, orientation, and environment.

Each new detection also acts as a stress test for Einstein’s gravity, especially when the masses and spins push theory.

Questions still open

Because the signal was brief and the models disagree, the exact story of how these black holes formed remains unsettled.

As the network keeps observing, more extreme mergers should arrive, and the community will learn which formation channels dominate.