When the space shuttle Columbia began its journey home on February 1, 2003, the seven astronauts on board were expecting a routine landing and, afterward, well-earned time with family and friends.

They had just wrapped up an intensive science mission in orbit. Instead, the orbiter broke apart over Texas and Louisiana, and the crew never made it back.

So what did the astronauts actually know in those final minutes? And why do those moments still matter for the way we study Earth and space today?

A science mission that never came home

Columbia’s STS 107 flight was not a construction run to the International Space Station. It was a dedicated research mission that spent 16 days in orbit carrying more than 80 experiments in microgravity, Earth and space science, technology and astronaut health.

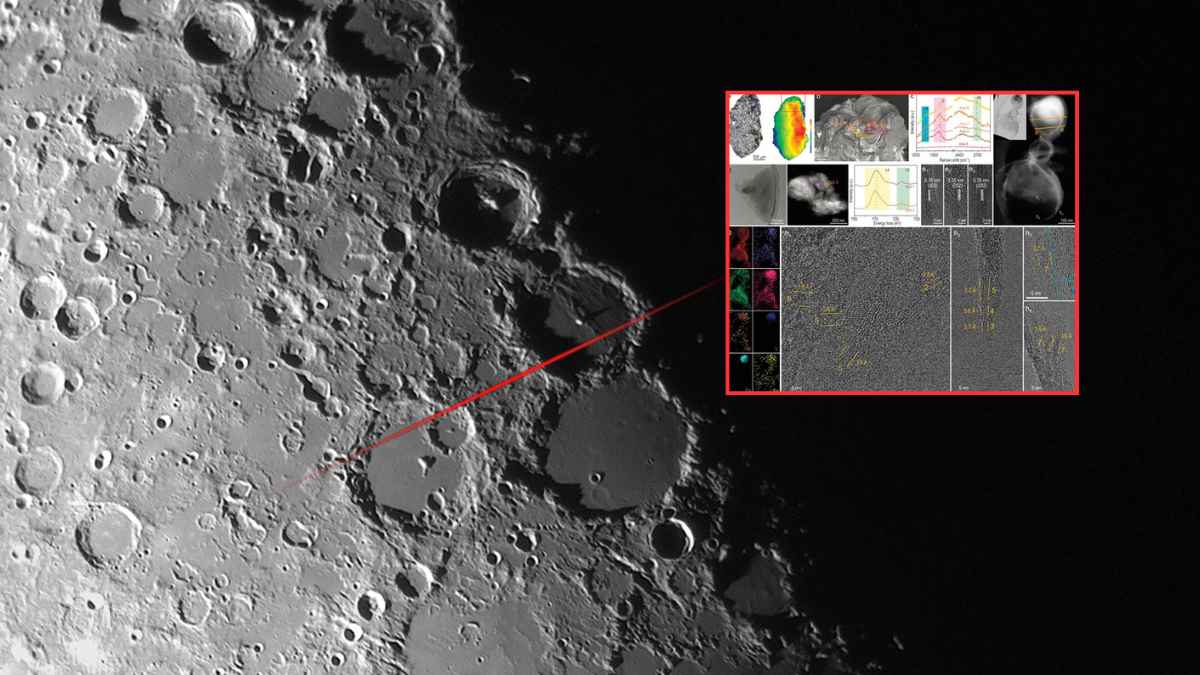

Inside the Spacehab research module, the crew studied everything from how flames behave without gravity to how cancer cells and bone tissue grow and change in space. Some experiments looked directly at our planet.

The Mediterranean Israeli Dust Experiment, for example, used special cameras to measure how airborne dust and aerosols affect clouds and rainfall, an important piece of the climate puzzle. Another set of instruments watched strange flashes high above thunderstorms known as sprites, which link weather, upper atmosphere chemistry and the near-space environment.

Much of the data had already been transmitted to the ground before reentry. NASA later estimated that roughly a third of the science results survived because of this, even though the shuttle and most hardware were lost.

Foam, a hidden breach and a damaged wing

The chain of events that doomed Columbia started during launch. A chunk of insulating foam from the external tank struck the reinforced carbon panels on the leading edge of the left wing, creating a breach that went unnoticed at the time.

During reentry, superheated plasma entered through that opening and began eating away at the wing’s internal structure.

The shuttle’s computers initially compensated for the growing drag on the damaged side by trimming the control surfaces, so to outside observers everything still looked normal.

What the crew saw in the cockpit

According to NASA timelines and the Columbia Crew Survival Investigation, the first clear sign of trouble for the astronauts appeared not as a dramatic fire or sudden jolt, but as cockpit warning messages about tire pressure in the left main landing gear.

A detailed explanation by aviator and space history student Andy Burns, shared on Quora and reported by The Aviation Geek Club, lines up with that official sequence. He notes that as sensors in the left wing and landing gear were destroyed by the incoming plasma, readings began to look abnormal or dropped off entirely.

The shuttle’s reaction control thrusters then started firing in an effort to keep Columbia pointed correctly when the aero surfaces could no longer cope.

NASA’s own crew survival analysis concludes that the astronauts treated these developments as a serious systems problem, not as a guaranteed death sentence. One summary of the report states that “the crew was unaware of an impending survival situation prior to the loss of control,” and that their actions showed they were still focused on restoring vehicle control.

About 40 seconds separated the moment Columbia fell out of controlled flight and the rapid depressurization of the crew cabin which made survival impossible. The Columbia Crew Survival Investigation found that the cabin pressure dropped so quickly that the astronauts could not even finish closing their helmet visors. Loss of consciousness would have followed within seconds.

In other words, they almost certainly knew that something was badly wrong. They had very little time to realize that it could not be fixed.

Suits, survivability and lessons learned

The orange Advanced Crew Escape Suits the astronauts wore were designed to protect them during controlled bailout scenarios at relatively lower altitudes and speeds, not during the violent breakup of a spacecraft at roughly Mach 15 high above the atmosphere.

NASA’s investigation stressed that no crew action or different use of this equipment could have changed the outcome once the wing failed.

Where the report places responsibility is on vehicle design, organizational decisions and the need for better training on when to stop troubleshooting and switch mentally into pure survival mode. Those findings now feed directly into the way newer spacecraft are built, from reinforced crew cabins to more robust restraints, pressure suits and crashworthy data recorders.

Why it matters for our planet

At first glance, the Columbia story can feel distant from everyday concerns like air quality alerts or rising electric bills. Yet the mission’s science sits right in the middle of how we understand Earth’s changing environment.

Experiments on dust and aerosols, atmospheric flashes and ozone structure help refine climate and weather models that underpin everything from drought planning to renewable energy forecasting.

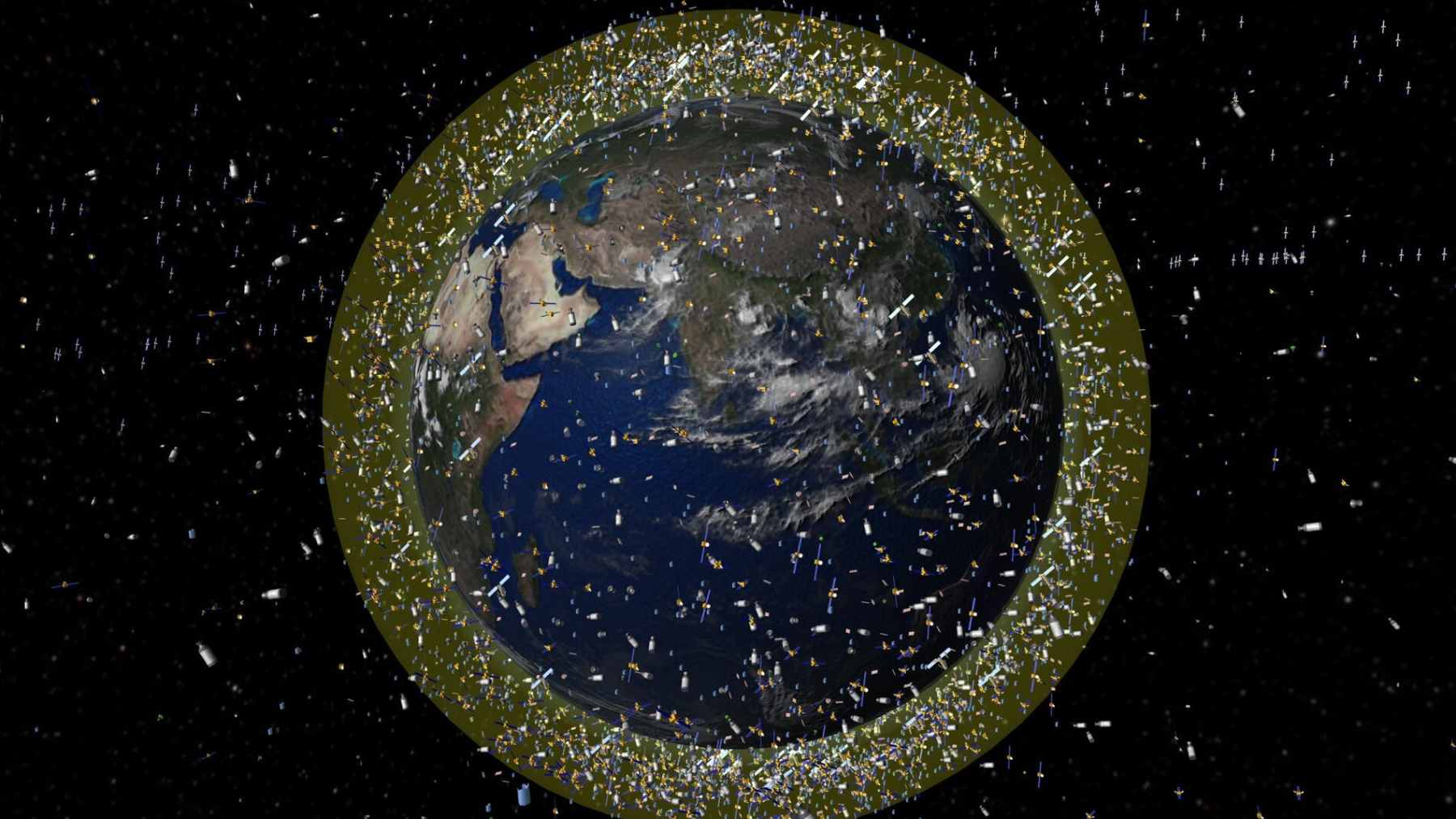

The safety work that followed the accident also supports the next generation of research flights, including satellites and crewed missions that monitor greenhouse gases, track storm formation and study how our atmosphere responds to pollution.

The more resilient those missions are, the more reliably they can watch over the planet we live on.

Two decades on, Columbia’s final minutes are not just a story of loss in the sky. They are also a hard-won lesson in how to protect the people who carry our scientific hopes into orbit, so their work can keep coming back home to Earth.

The official report was published by NASA.