Deep inside the ruined reactor 4 at Chernobyl, where radiation is still strong enough to keep people out, a black fungus is quietly thriving. The species, Cladosporium sphaerospermum, coats concrete and metal in one of the most radioactive buildings on Earth and seems to grow better the more radiation it receives.

To many scientists, that strange behavior hints that this fungus may be using radiation almost like plants use sunlight.

That idea has given rise to a bold hypothesis known as radiosynthesis, in which the pigment melanin would capture energy from ionizing radiation and feed the fungus. Over the past two decades, researchers have tested this concept in both nuclear ruins and on the International Space Station, collecting clues that melanin-rich fungi can survive and even flourish under intense radiation.

Yet even after all those experiments, no one has been able to prove that the fungus truly “eats” radiation rather than simply coping with it.

A black fungus thriving where humans cannot

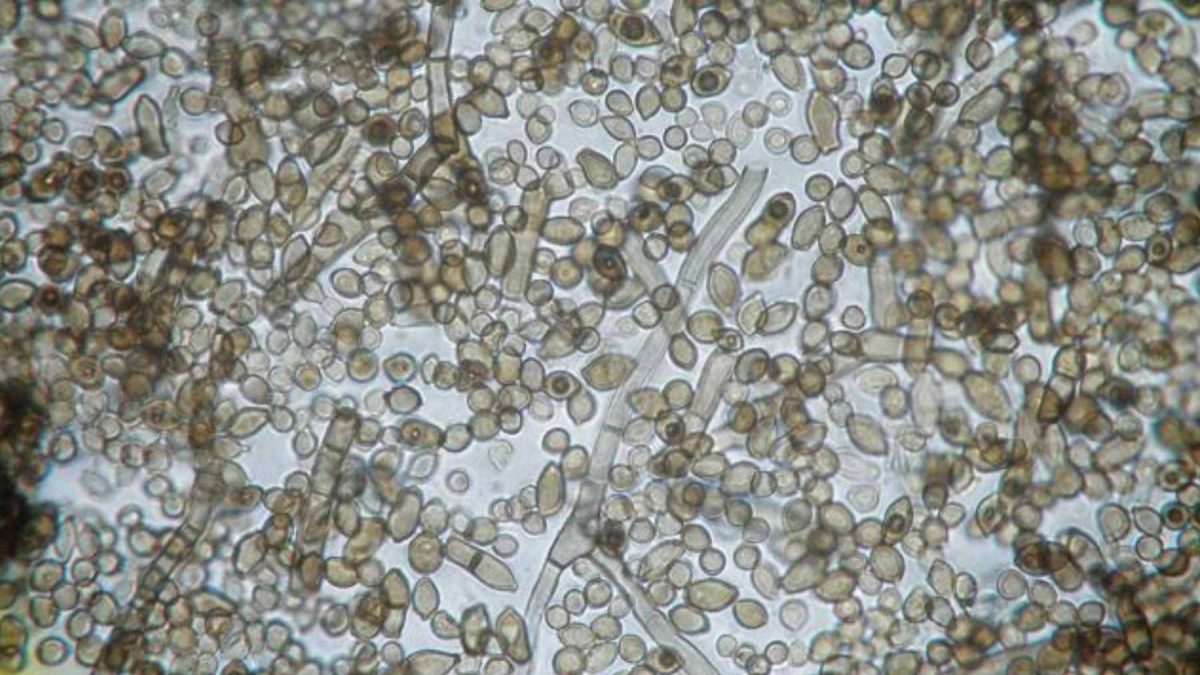

In the late 1990s, Ukrainian microbiologist Nelli Zhdanova and her team sampled the concrete shell built around Chernobyl’s destroyed reactor. They identified dozens of fungal species inside this huge “sarcophagus,” most of them dark and packed with melanin, the same pigment that colors human skin, hair, and eyes.

Cladosporium sphaerospermum showed up most often in those samples and also carried some of the highest levels of radioactivity.

Ionizing radiation in that building is still high enough to damage human DNA within minutes. For most organisms, such radiation breaks chemical bonds, shreds molecules, and triggers lethal mutations. Some melanin-rich fungi even grow toward radiation sources rather than away from them, a behavior known as radiotropism.

These observations raised an obvious question for researchers. If melanin-rich fungi are not just surviving, could they be extracting useful energy from the radiation that bathes them?

What scientists mean by “radiosynthesis”

Radiosynthesis is the idea that melanin in fungal cells plays a role similar to chlorophyll in plants. In this picture, melanin would absorb high-energy radiation and change its own electronic structure in a way that lets the fungus use some of that energy for growth.

The term came into wider use after a 2007 laboratory study led by radiopharmaceutical researcher Ekaterina Dadachova showed that ionizing radiation altered melanin’s electronic properties and boosted growth in several melanized fungi under controlled conditions.

In a follow up review, Dadachova and immunologist Arturo Casadevall, then working at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, argued that melanized fungi from Chernobyl and other extreme environments seem unusually good at coping with radiation.

They pointed out that exposure can raise fungal metabolic activity and change gene expression, suggesting that melanin is doing more than acting as a simple shield.

Even so, scientists stress that this is still a hypothesis rather than a proven energy pathway. No research team has yet shown that these fungi use radiation alone to fix carbon, ramp up their metabolism, or store extra chemical energy in a clear and direct way.

As engineer Nils Averesch and his colleagues put it, “actual radiosynthesis has not yet been demonstrated,” and the details of any energy gain remain unresolved.

Space station tests hint at a natural radiation shield

To see how Chernobyl-style fungi behave off Earth, Averesch led an experiment that grew Cladosporium sphaerospermum aboard the International Space Station. Radiation sensors sat beneath a thin fungal layer and beneath a fungus-free control sample so that any shielding effect could be measured.

After several weeks in orbit, the fungal side showed roughly a 2% drop in detected radiation and a modest growth advantage compared with identical cultures on the ground.

The goal of that space study was not to prove radiosynthesis. Instead, the team wanted to test whether living fungi could act as light, self-repairing radiation shields for future missions to the Moon or Mars.

Their results suggest that combining melanin-rich biomass with local materials like Martian soil might reduce the amount of heavy shielding that spacecraft need to carry from Earth.

The mechanism behind the shielding is still unclear. Melanin could simply be absorbing or scattering some incoming particles, or the fungus could be changing its own structure as it responds to stress. What it does not do is magically “clean up” radioactivity, since the radioactive atoms themselves remain in place while the fungal layer only reduces the dose behind it.

Different fungi, different survival tricks

Cladosporium sphaerospermum is not alone in its odd relationship with radiation. In Dadachova’s experiments, the black yeast Wangiella dermatitidis grew faster when exposed to very high levels of ionizing radiation compared with non-melanized mutants.

Another species, Cladosporium cladosporioides, increased its melanin production under gamma and ultraviolet radiation without showing the same jump in growth.

Those differences hint that there is no single, universal fungal trick for dealing with radiation. Instead, each species may have evolved its own mix of stress responses, from thickening its melanin-rich cell walls to adjusting metabolism so it can ride out harsh conditions. For the most part, melanin still looks like a versatile survival tool rather than a guaranteed energy source.

For Cladosporium sphaerospermum, the big question remains whether it truly taps radiation as fuel or simply uses melanin to endure one of the harshest environments on the planet and in space. Either way, its success in places where no one would ever plan a picnic shows how adaptable life can be.

The main study on the space station experiment has been published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology.