Have you ever dragged your fingers through sand and felt something was there before you actually hit it? According to a new line of research, that hunch might not be in your head. It might be a real, measurable sense that scientists are now calling “remote touch.”

A team from Queen Mary University of London and University College London has shown that people can detect an object buried in sand before their fingers make contact with it, and they do it with about 70% precision. This ability looks similar to what shorebirds such as sandpipers use to find prey hidden beneath the sand.

If those results hold up in future studies, they do more than add a cool twist to the idea of five senses. They could reshape how robots explore dark, dusty, or dangerous places where cameras and lasers struggle.

A sense borrowed from shorebirds

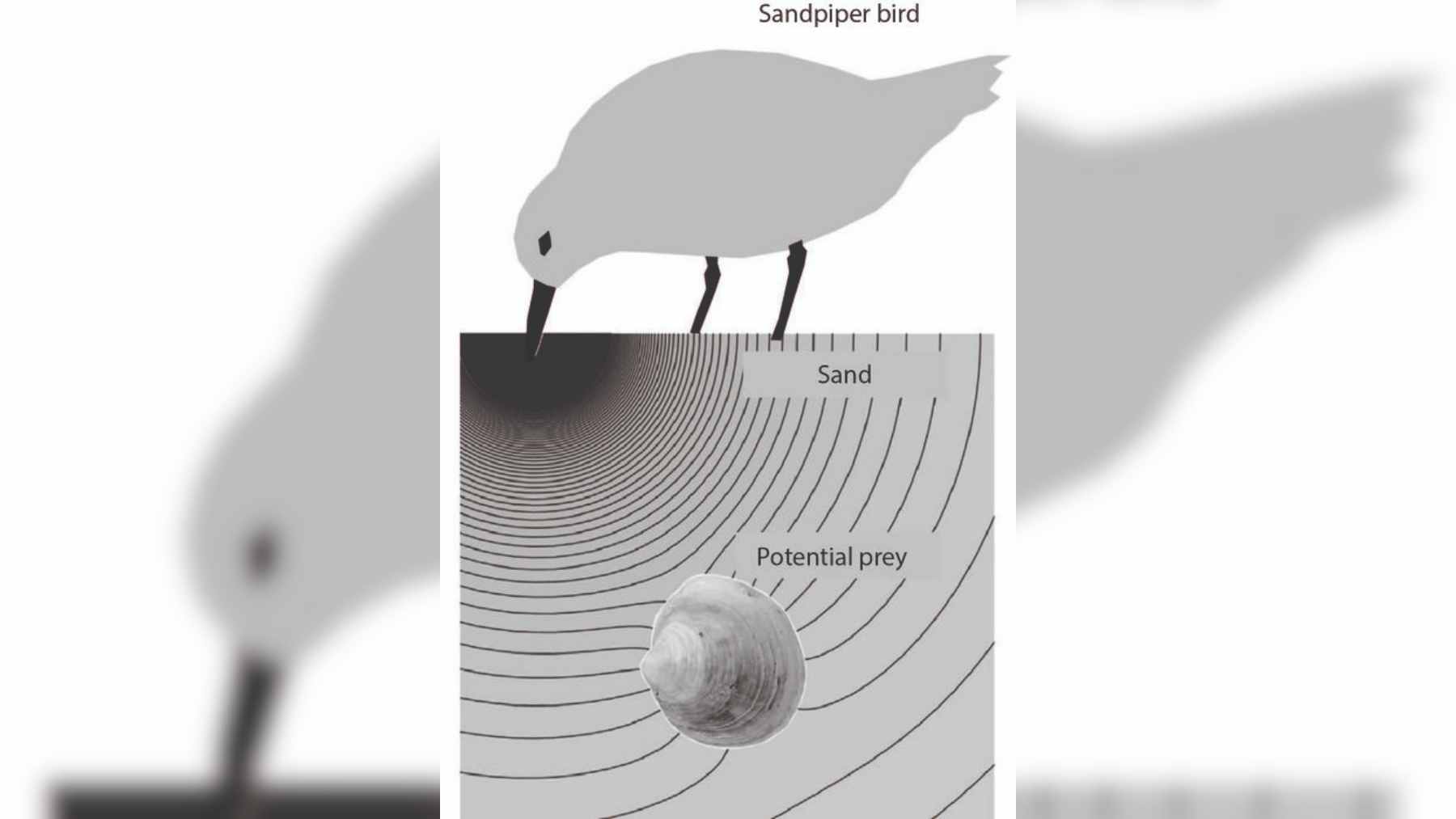

Touch is usually described as a “short range” sense. You press on a surface, it pushes back, and your nerves tell your brain what you hit. But in nature, the picture is already more complicated. Shorebirds probe wet sand with their beaks and pick up tiny pressure changes that reveal worms and other buried prey.

The new work tested whether human hands might share something similar when they move through loose material. Researchers refer to this ability as remote touch, because the skin is picking up mechanical changes in the environment that originate at a distance from the body.

The signal travels through the grains, not through direct contact with the hidden object.

In practical terms, imagine a buried toy at the beach. As your hand glides through the sand, the grains in front of your fingertips shift differently near that toy, creating a narrow zone where the sand subtly stiffens or flows in a new way. The study shows that our nervous system can read those almost invisible changes.

How the sand experiment worked

In the human experiment, twelve volunteers sat at a setup that looked simple from the outside: a long box filled with dry sand and a narrow slit on top for a single finger. Hidden somewhere along the path was a small cube, buried ahead of where the finger would travel.

Participants were asked to rake their index finger slowly through the sand and press a button the moment they felt that something under the surface “felt different.” Only afterward would their finger reach the cube, if it was there at all.

The researchers also modeled how grains move and pile up when a finger pushes through them, predicting that useful mechanical cues could extend several centimeters in front of the fingertip.

The results suggest those predictions were right. Human participants detected buried objects with a precision of 70.7% within the range where physics said detection should be possible, with a median distance of about 2.7 centimeters between the point of detection and the cube.

At the same time, both the modeling and the behavior pointed to sensitivity close to the physical limit of what tiny mechanical reflections in sand can carry.

It is a kind of superpower. You would not notice it when you grab a mug or tap your phone, but in the right conditions the skin on your hand can feel the world a little farther out than most of us realize.

Humans vs robots in the sand

To see how humans stack up against machines, the team ran a second experiment using a robotic arm equipped with a tactile sensor. The robot followed a similar path through sand, while an artificial intelligence model known as a Long Short-Term Memory network tried to learn which subtle force patterns meant “object present” and which meant “nothing there.”

On paper, the robot reached slightly farther than people. It could detect objects at distances of around seven centimeters, with a median of about six centimeters from the buried cube. But that longer reach came at a cost.

The system produced many false alarms and ended up with only about 40% precision, far below human performance.

So humans and robots each excelled in their own way. The robot was good at feeling weak signals over a bigger area. People were much better at telling real targets from noise. For engineers, that combination is gold.

It suggests that human tactile abilities can serve as a benchmark for smarter robotic touch, especially in places where vision is blocked by dust, mud, or rubble.

Why this “seventh sense” matters

At the end of the day, this research is not about parlor tricks with sand. It points to new possibilities in assistive technology and field robotics. Members of the team highlight potential uses that range from locating fragile archaeological artifacts without digging aggressively into the soil to probing Martian regolith or ocean floors where visibility is poor and direct contact is risky.

You can also imagine more grounded applications. A prosthetic hand that can sense obstacles hidden in debris before hitting them could help users navigate cluttered real-world environments. A search-and-rescue robot that “feels” voids in collapsed buildings might find trapped people faster while disturbing less material.

The same basic physics that lets a fingertip read ripples in sand could eventually flow into the design of gloves, grippers, and smart tools.

Do humans really have a brand new sense?

Scientists are careful about how they use that phrase “seventh sense.” Many researchers already argue that humans have far more than five senses, counting proprioception, balance, and temperature among others.

For the most part, this new work suggests that touch is more flexible and far reaching than textbook diagrams imply, rather than unveiling a magical new channel.

Still, the idea that our skin can pick up information from objects we never actually touch is a meaningful shift. It nudges neuroscience to rethink how the brain maps the space around the body and invites robotics to borrow strategies our nervous system has apparently used all along.

Next time you run your hand through sand at the beach or over a box of rice in the kitchen, it might be worth paying attention to that tiny change in resistance that makes you pause for a second. There could be more happening between your fingertips and the hidden world beneath than you ever guessed.

The press release was published on SciTechDaily.