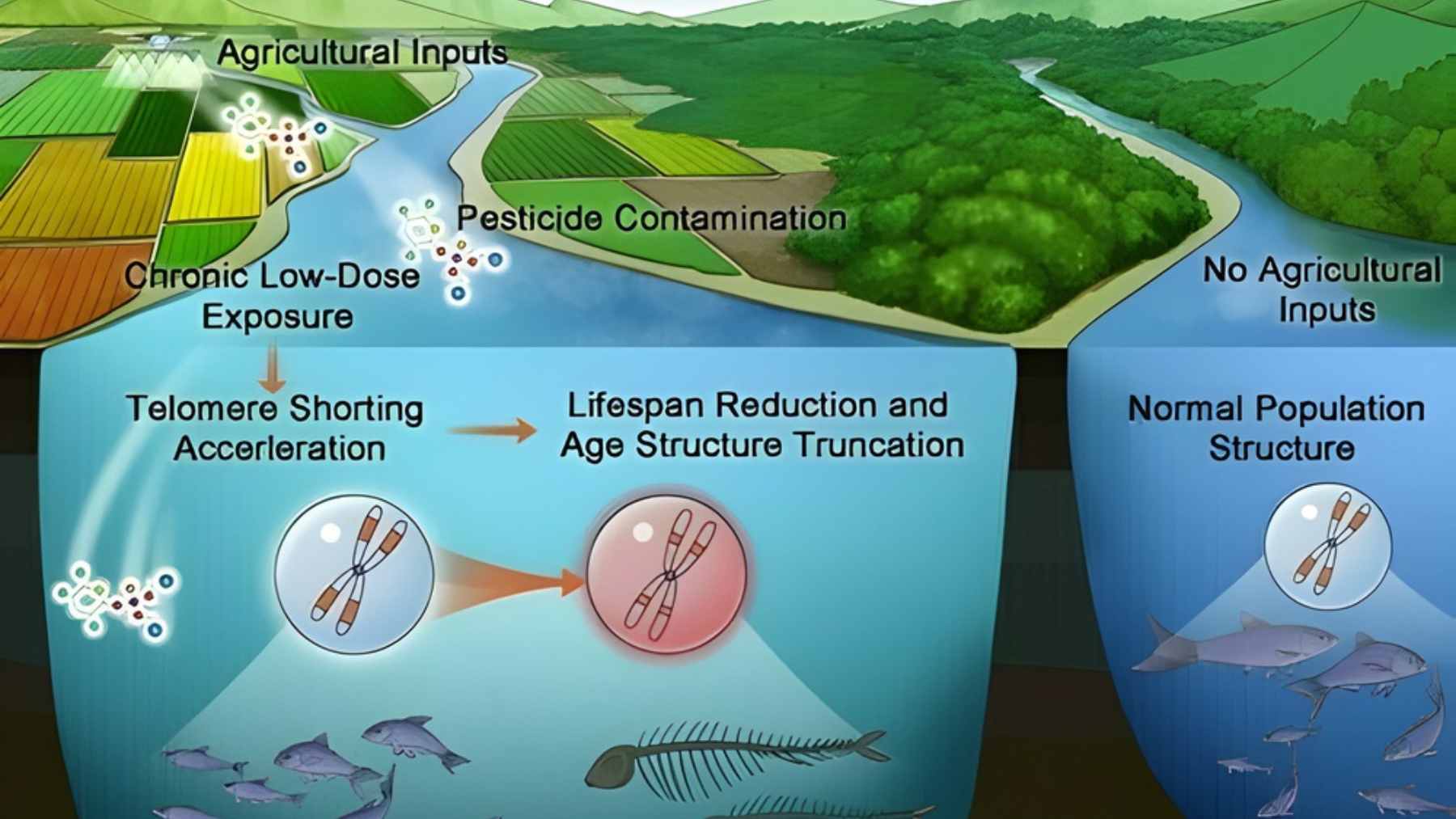

Low levels of farm chemicals that wash off fields are often labeled safe. A new study suggests that may not be true for the fish living downstream, even when the water looks clear and healthy to us.

Researchers have found that a common agricultural insecticide called chlorpyrifos can make wild fish grow old faster at the cellular level.

A team led by biologist Jason Rohr at the University of Notre Dame analyzed more than twenty thousand lake skygazer fish in China, then backed up their field work with controlled lab experiments, building a detailed picture of how long-term pollution trims away years of life.

What scientists found in Chinese lakes

In the field, scientists focused on lake skygazer fish, a relative of carp that lives in freshwater lakes. According to a new Science study, they collected thousands of fish from three nearby lakes that differed in how contaminated they were with farm chemicals, then compared age and health markers in each population.

The more polluted the lake, the fewer older fish they found, even though younger fish were still present.

The team measured a wide range of pesticides in the fish and in the surrounding water. Chlorpyrifos stood out as the only compound that consistently matched signs of aging in the fish, including a skewed age structure packed with young animals and very few older survivors. Other pesticides were present but did not show the same tight link with these aging markers.

They also zoomed in on the fish chromosomes. Fish in contaminated lakes had shorter telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of DNA strands that act a bit like the plastic tips on shoelaces and wear down as cells divide.

In the liver, they saw higher levels of lipofuscin, a brownish buildup of old proteins often described by scientists as cellular junk, another classic sign that tissues are growing old before their time.

How low doses of chlorpyrifos accelerate aging

Chlorpyrifos is an organophosphate insecticide used for decades to kill crop pests. While the European Union and the United Kingdom have banned it, the compound is still used in China and parts of the United States, often at levels that meet current freshwater safety standards.

The new results suggest that even these low background concentrations can chip away at fish lifespans over many months.

To understand the mechanism, the researchers looked again at telomeres. Telomeres shorten naturally as animals age or face long-term stress, and when they become too short, cells lose the ability to repair themselves and to divide in a healthy way.

In the study, fish exposed to more chlorpyrifos had noticeably shorter telomeres than fish of the same chronological age from cleaner lakes, a sign that their biological clock was running faster.

Lab experiments helped confirm that chlorpyrifos itself was to blame. Rohr and lead author Kai Huang exposed fish to low, steady doses of the pesticide for weeks at concentrations similar to those measured in the wild and saw progressive telomere shortening, more lipofuscin, and lower survival, especially in fish that were already older.

When they used short, high-dose exposures, the chemical caused quick poisoning and death but did not leave the same aging fingerprint on the cells.

Why this matters for fish populations and for people

For wild fish populations, losing older individuals can be a serious problem. Older fish often produce more eggs, carry valuable genetic diversity, and help stabilize populations through bad years, a bit like experienced members of a community who know how to handle a crisis.

If low-level pesticide pollution keeps quietly removing those older fish, lakes may look full on the surface while their long-term resilience is slowly eroding.

The findings also put pressure on how regulators think about chemical safety. Most tests focus on short-term exposure and ask whether an animal dies outright or shows obvious toxicity in the first hours or days, which can miss subtle damage from tiny doses that never go away.

Earlier work, including a 2018 study, has already shown that the chlorpyrifos levels used in this research sit below many measurements from rivers and lakes around the world, which means these conditions are far from rare.

There is a human angle here too. Telomere biology is remarkably similar across vertebrates, and the authors note that the same types of processes that age fish cells also play a role in age-related diseases in people.

That does not mean chlorpyrifos is proven to speed up human aging, but it does mean experts are taking a harder look at everyday, low-level exposures in drinking water, food, and nearby farms. As Rohr put it, “Our results challenge the assumption that chemicals are safe if they do not cause immediate harm,” a reminder that the real risk may build up quietly over time.

The official press release was published on news.nd.edu.