A tiny ocean microbe is forcing scientists to rethink what “being alive” really means. The newly described organism, Candidatus Sukunaarchaeum mirabile, has the smallest known genome of any archaeon and seems to survive with a bare minimum of genes while leaning almost entirely on its host.

It sits in a strange middle ground between living cell and virus, and that is shaking up biology.

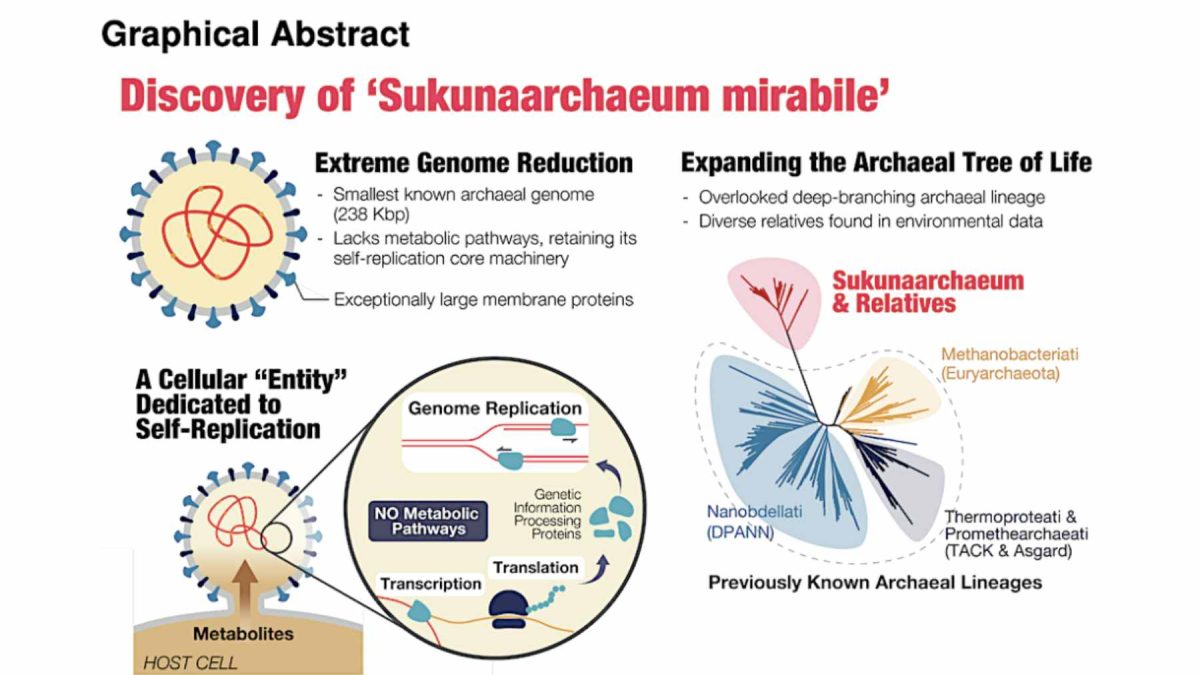

Researchers based in Japan and Canada uncovered Sukunaarchaeum while sequencing DNA from a marine dinoflagellate called Citharistes regius, part of ordinary ocean plankton. In that genetic soup they noticed fragments that did not match any known species and eventually pieced together a tiny circular genome of about 238 thousand base pairs.

That is less than half the size of the previous record holder among archaea, Nanoarchaeum equitans, which carries roughly 490 thousand base pairs. So far the microbe is known only from its genome and has not yet been seen or grown in culture.

A genome stripped almost to the bone

Once the team had the full sequence, they found a striking pattern. Most recognizable genes were not about feeding, breathing or building cell parts. Instead more than two-thirds of the known genes are devoted to copying and reading DNA, including the machinery for replication, transcription and translation.

In plainer words Sukunaarchaeum can copy its own genome and build ribosomes to make proteins, yet it seems to lack the usual pathways that cells use to make energy or basic nutrients.

That kind of ultra-minimal setup has echoes in other recent work on genome reduction in parasites and symbionts, where researchers have documented bacteria that have also shed large parts of their metabolism. But Sukunaarchaeum takes this strategy to a new extreme that has caught the attention of microbiologists and origin-of-life experts alike.

For readers who follow cutting-edge genetics, it feels a bit like the “genetic surprise of the year” all over again, similar to how one featured study showed that what we thought was one fish species was actually three, split by DNA and anatomy across Amazonian rivers in a separate genetic study.

Between cell and virus

Because it carries almost no metabolic toolkit, Sukunaarchaeum appears to live as a holoparasite on its host dinoflagellate, drawing in ready-made molecules while focusing its own resources on self replication.

That lifestyle resembles a virus, which also depends completely on a host. At the same time this microbe keeps key cellular traits, including its own replication proteins, ribosomal RNA and what looks like a membrane around its DNA.

Scientists see it as one of the closest cellular imitators of viral behavior described so far, blurring the long-standing boundary between minimal cells and viruses. So is it really alive, or not?

Stories about organisms that seem to sit on the edge of major definitions are becoming more common. Recent coverage in Popular Mechanics and other outlets has framed Sukunaarchaeum as a “creature at the fringes of life,” while lab groups point out that similar questions pop up when we discover new species in remote ecosystems, such as the completely new animals found on a jungle expedition reported in another science feature.

Hidden diversity in a drop of seawater

Sukunaarchaeum is probably not alone. When the team searched global ocean DNA surveys, they found many related sequences that seem to form a previously overlooked branch of the archaeal tree.

That suggests similar ultra-reduced parasites may be common in plankton communities that quietly drive marine food webs and global cycles of carbon and nutrients. For anyone picturing the sea as “just water,” it is a reminder that each drop can hold entire worlds of microscopic life we have barely begun to map.

The idea that we are still underestimating this hidden diversity does not stop at microbes. In recent months, scientists have also revealed unexpectedly-complex chemistry in lunar dust and surprising patterns in animal genomes, from carbon-rich Moon samples to a simple purple glow that helps destroy stubborn materials at room temperature.

All of it hints that the planet and its surroundings still hold plenty of surprises.

Rethinking the minimum for life

For origin-of-life research, Sukunaarchaeum offers a rare glimpse of how far a cell can shed genes and still keep a distinct identity.

Some experts see it as tentative support for the idea that at least some viruses might descend from parasite cells that gradually lost their metabolic genes while keeping a hardcore replication system, a possibility discussed in early commentary from outlets like Science and lab summaries at the University of Tsukuba and partners.

Others note that the work is still a preprint and has not yet passed peer review, so any grand rewrite of biology textbooks will need to wait.

In the meantime, techniques used to spot this microbe are feeding into broader efforts to track microscopic life and even to design new ways to process waste and pollutants, a theme that echoes in lab breakthroughs such as the room temperature material destruction method highlighted by environmental researchers.

The study was published on bioRxiv.