More than eighty years after a teenager squeezed through a hole in a tree in rural France, the cave he found is still rewriting how we treat ancient art. The painted chambers of Lascaux cave are now closed to almost everyone, yet their walls are more visible than ever in museum replicas and virtual tours.

How do you keep a place that old alive without letting millions of visitors breathe all over it. That question, to a large extent, now sits at the heart of the Lascaux story.

The 1940 discovery of Lascaux cave

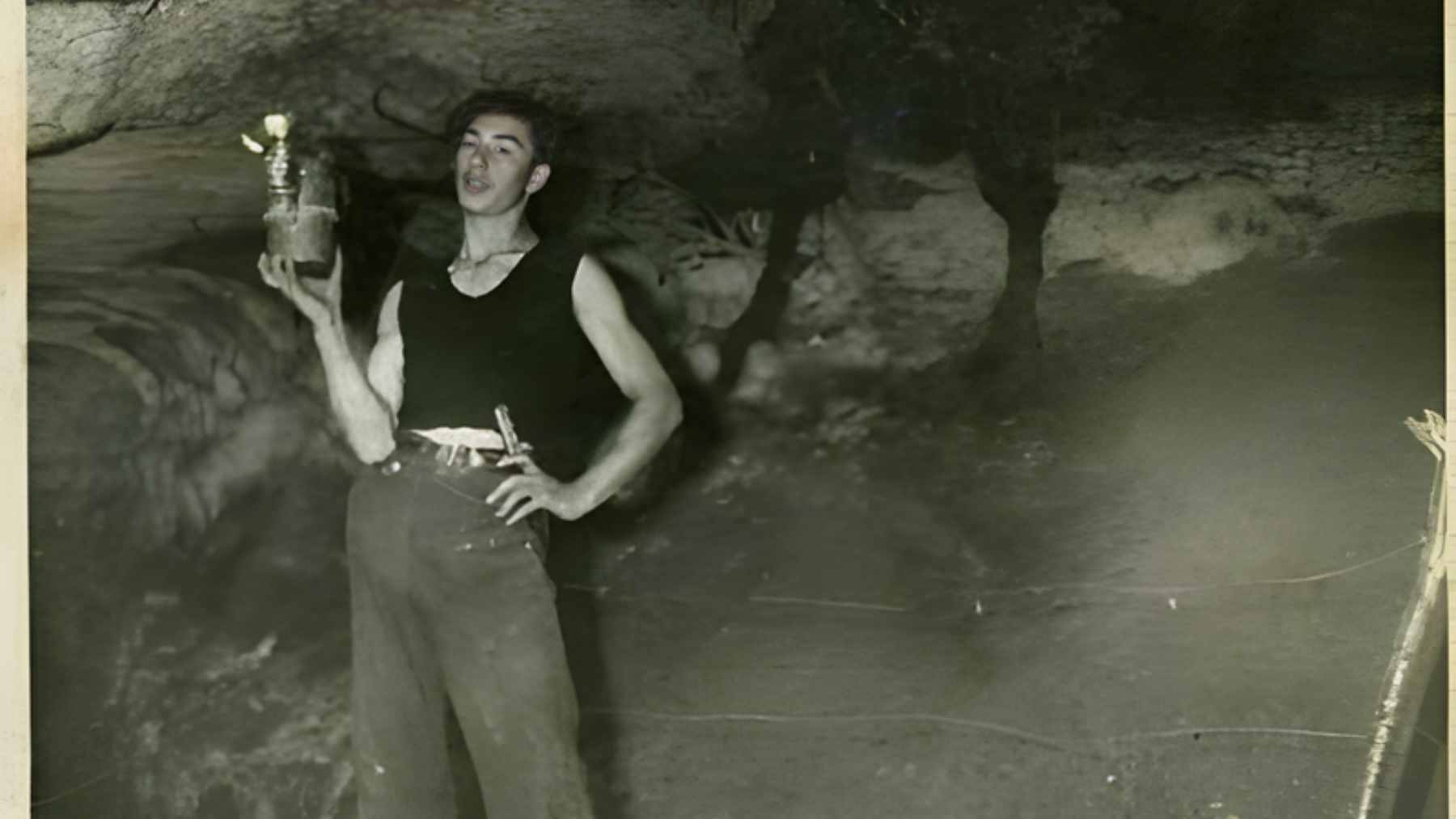

On September 12, 1940, eighteen-year-old Marcel Ravidat followed his dog Robot into a hole near a fallen tree on a wooded slope above the village of Montignac in southwestern France.

A few days later he returned with three friends Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel and Simon Coencas and widened the opening. Inside they found chambers packed with vivid animal paintings that had not seen human eyes for roughly 17,000 to 19,000 years.

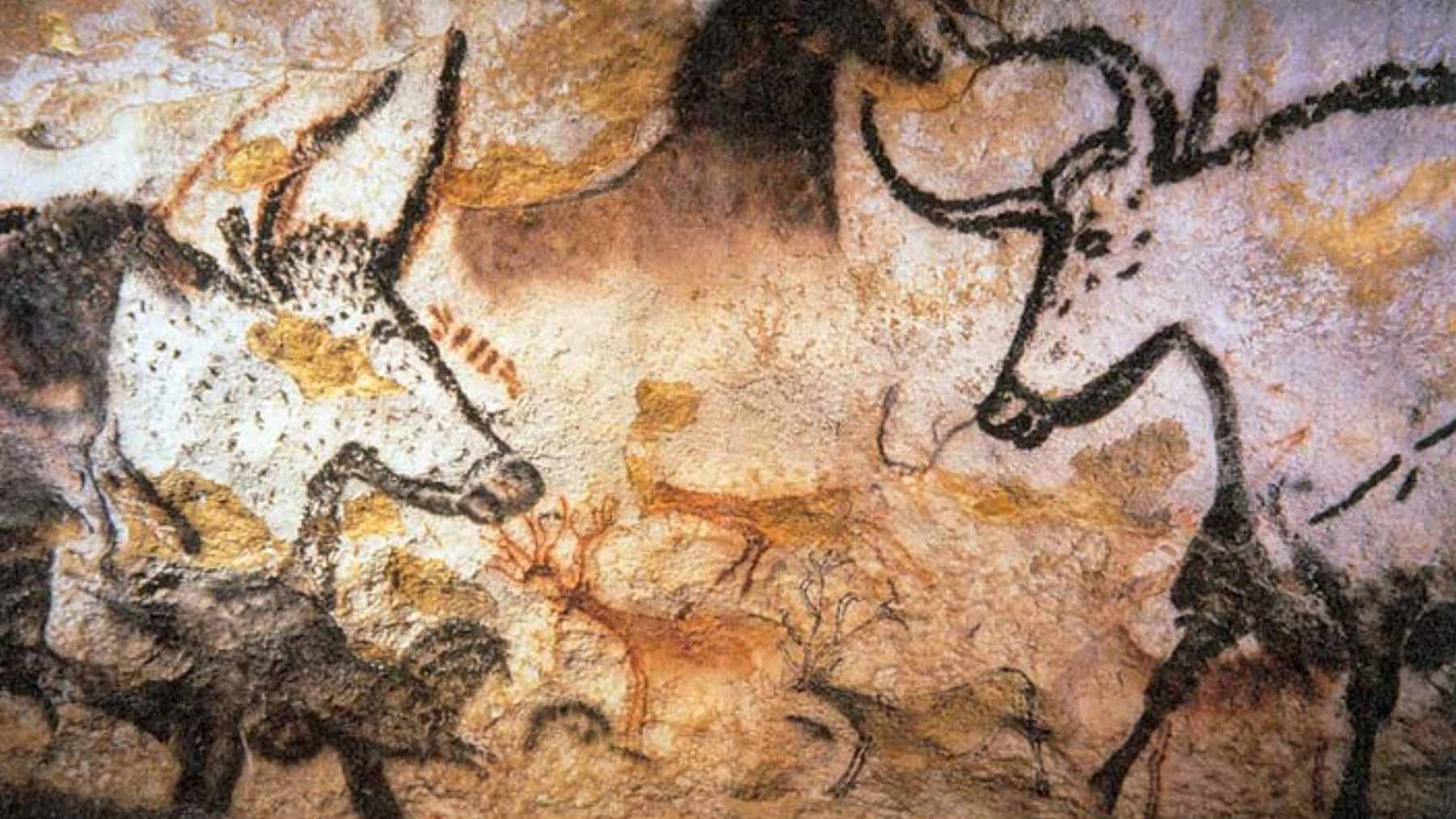

Ice Age cave paintings and Magdalenian art

Archaeologists later linked the art to the Magdalenian culture of the late Ice Age. The Lascaux system contains more than 2,000 images and about 6,000 engraved or painted figures across nine sections, including the Hall of the Bulls, the Nave and the Shaft.

Many show aurochs, deer, horses, ibex and big cats in motion. Some stretch well over six feet, which meant prehistoric artists probably built simple scaffolding, ground pigments such as red ochre, hematite, charcoal and manganese oxide, and worked by firelight or oil lamps to reach the ceilings.

Archaeologists and the French Ministry of Culture

Within a week of the discovery, the boys alerted local teacher and amateur prehistorian Léon Laval. He recognized the style as prehistoric and contacted Henri Breuil, a leading archaeologist who confirmed the cave’s importance in records held by the French Ministry of Culture.

From there, Lascaux quickly became a touchstone for Paleolithic art research and, in popular writing, something close to a prehistoric Sistine Chapel.

Tourism damage and why Lascaux closed

In 1948 the cave opened to visitors. The crowds came fast. At one point more than 1,200 people a day shuffled through the narrow spaces, each bringing warm breath, carbon dioxide and moisture into a system that had stayed remarkably stable for thousands of years.

Green algae began to bloom on the walls. In 1963, faced with clear signs of damage, the French government shut the original cave to mass tourism and limited access to conservation staff and a small number of researchers.

Conservation threats and the Fusarium fungus outbreak

Closing the door did not solve everything. In 2001, work on the air conditioning system inadvertently introduced a Fusarium fungus that spread across floors, walls and ceilings.

A report from ABC Science in 2003 described how specialists turned to fungicides and later an antibiotic called polymyxin to hold the outbreak in check while trying not to harm the paintings themselves.

A detailed 2007 study led by mycologist Joëlle Dupont in the journal Mycologia identified at least three members of the Fusarium solani species complex in the cave using genetic markers, noting this was the first time such fungi had been documented in a decorated prehistoric site.

Lascaux replicas and digital twins

Conservation now drives almost every decision about Lascaux. Yet the desire to see the images has not faded. So France built what are essentially twins. Lascaux II, near the original entrance, recreates key chambers using traditional materials. Lascaux III takes selected panels on the road as a traveling exhibition.

The most ambitious version, Lascaux IV at the International Centre for Parietal Art (Lascaux IV), offers a nearly complete replica enhanced with high-resolution 3D modeling and spatial sound so visitors feel as if they are stepping into the real cave without ever touching it.

Lascaux IV and immersive museum experience

Designers argue these copies are not just consolation prizes for people who missed the original ticket line. Exhibition designer Dinah Casson, whose firm Casson Mann worked on Lascaux IV, put it bluntly in one interview: “You see this, or you see nothing,” a line that captures how little choice there is if the paintings are to survive.

She has also pointed out that many visitors will simply be holidaymakers looking for something to do on a rainy day, not only specialists in Ice Age art, which makes an engaging, comfortable replica even more important.

What the cave paintings might mean

The meaning of the images remains an open debate. Some panels sit deep inside the cave in spots that now require artificial lights and constructed walkways, which has encouraged ideas about rituals, storytelling or secret gatherings rather than simple decoration.

An explainer by art historian Frances Fowle, published in The Conversation in 2025, notes that overlapping figures and remote placement in caves like Lascaux may hint that the act of painting held symbolic value of its own.

France’s official archaeological site groups current thinking into broad possibilities that include hunting magic, territorial markers and early narrative imagery, but stresses that none can be proven while we lack written records from the people who painted the walls.

Why digital access matters for heritage preservation

For most of us, the practical message is simple. The original cave is off limits because human bodies change its delicate climate and, once a figure is lost, there is no way to repaint a seventeen-thousand-year-old aurochs.

The replicas and virtual tours are not second best; in everyday terms they are the only way to let school groups, tour buses and curious night owls with laptops share in the art without repeating the damage of the 1950s. At the end of the day, what these digital and physical doubles try to do is keep a fragile underground gallery alive while still letting the rest of us look.

The study was published in Mycologia.