If you have ever hit that heavy afternoon slump and dreamed of a quick nap, you are not alone. According to endocrinologist Christos Mantzoros, a short siesta is not just a cultural habit in southern Europe. In his words, sleeping after lunch has been linked to lower stress, which in turn is good for metabolism.

That simple everyday habit sits on top of something much bigger. Mantzoros is a professor of internal medicine at Harvard Medical School and editor in chief of the journal Metabolism.

He recently delivered the closing lecture at the XIII International Lipodystrophy Symposium in Santiago de Compostela, an event organized by patient group AELIP and the research center CiMUS at the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

Rare fat disorders as a warning signal

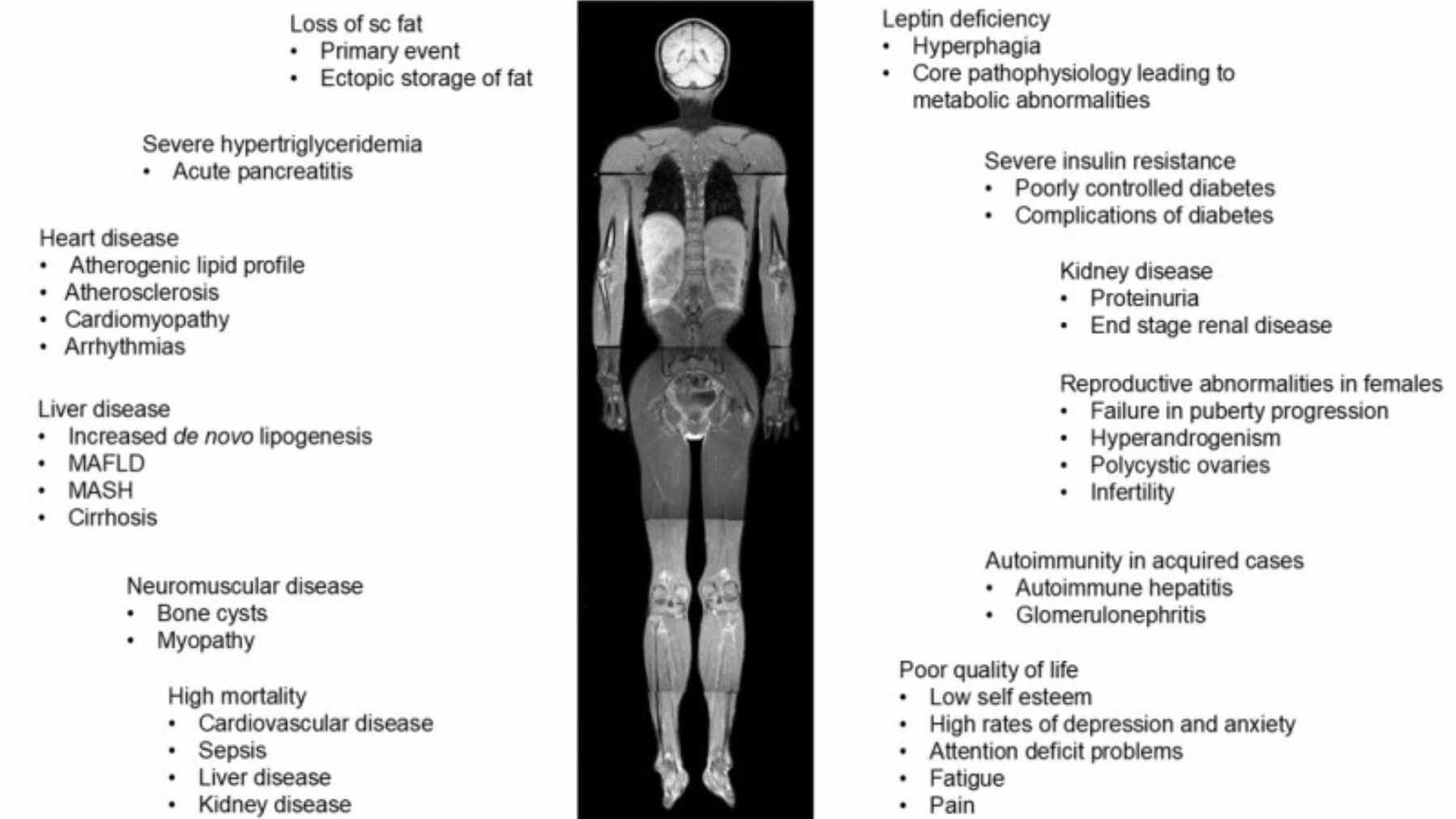

Mantzoros describes lipodystrophies as the tip of the iceberg of metabolic disease. These are rare conditions where body fat is missing in some places and often misplaced in others.

When the usual fat under the skin cannot store more energy, the overflow ends up in the liver, muscles and blood vessels. That extra fat in the wrong place drives insulin resistance, fatty liver and a higher risk of heart attack and stroke.

Think of it like a small storage unit at home. Once every shelf is jam packed, the boxes move into the hallway and living room, where they trip you up. In the body, that clutter shows up as elevated triglycerides, rising blood sugar and chronic inflammation.

For researchers, these rare cases act like a magnifying glass. Problems that take decades to appear in common obesity show up early and dramatically in lipodystrophy. Studying them has helped open what Mantzoros calls the black box of human metabolism.

From fat hormones to blockbuster drugs

Over the past thirty years, scientists have learned that fat tissue is not just passive padding. It behaves like an endocrine organ that releases powerful hormones. One of the best known is leptin, which signals how full the fat stores are.

In people with generalized lipodystrophy, leptin levels are extremely low, and clinical trials show that replacing this hormone with the drug metreleptin improves severe metabolic complications.

Another hormone, adiponectin, tends to be lower when harmful visceral fat around the organs increases. Together, leptin and adiponectin have become key markers that help doctors understand not just how much fat a person has, but where that fat sits and how risky it is.

Today the focus is shifting toward hormones made in the gut. Drugs based on GLP‑1 and related molecules, such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, mimic intestinal signals that reduce appetite and improve insulin sensitivity.

Large trials in people with obesity have found that these medicines can lead to average weight losses around fifteen to twenty percent and, in the case of semaglutide, cut major cardiovascular events by about twenty percent.

Mantzoros expects the next wave to combine several treatments and eventually include medicines that protect or even build muscle mass. At the same time, he warns that rapid weight loss can also reduce muscle and bone, which is not what doctors want to see.

Where daily habits and the siesta fit in

For most people, the story does not start with an injection. It starts with daily habits. Mantzoros highlights four pillars that, to a large extent, come straight from everyday Mediterranean life. First, a balanced Mediterranean-style eating pattern.

Second, regular movement, even something as simple as six to eight thousand steps per day. Third, avoiding alcohol and tobacco.

And finally, a short midday nap, especially in countries where heat and work schedules make that pause part of the routine.

So is napping always healthy? The science is more nuanced than a simple yes or no. Reviews of nap research suggest that short daytime naps around twenty to thirty minutes can lower stress, improve alertness and support performance, especially in people who did not sleep enough at night.

On the other hand, large population studies link very long daytime naps with higher rates of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. That risk seems to rise when naps last more than an hour or when night sleep is poor.

At the end of the day, Mantzoros is not arguing that a siesta alone will fix obesity, diabetes or fatty liver.

His message is that rare disorders like lipodystrophy help scientists build better treatments, while simple, low-cost habits such as walking more, eating in a Mediterranean way and taking a brief, restorative nap can ease stress and support the same metabolic systems those drugs target.

The official statement was published on AELIP.