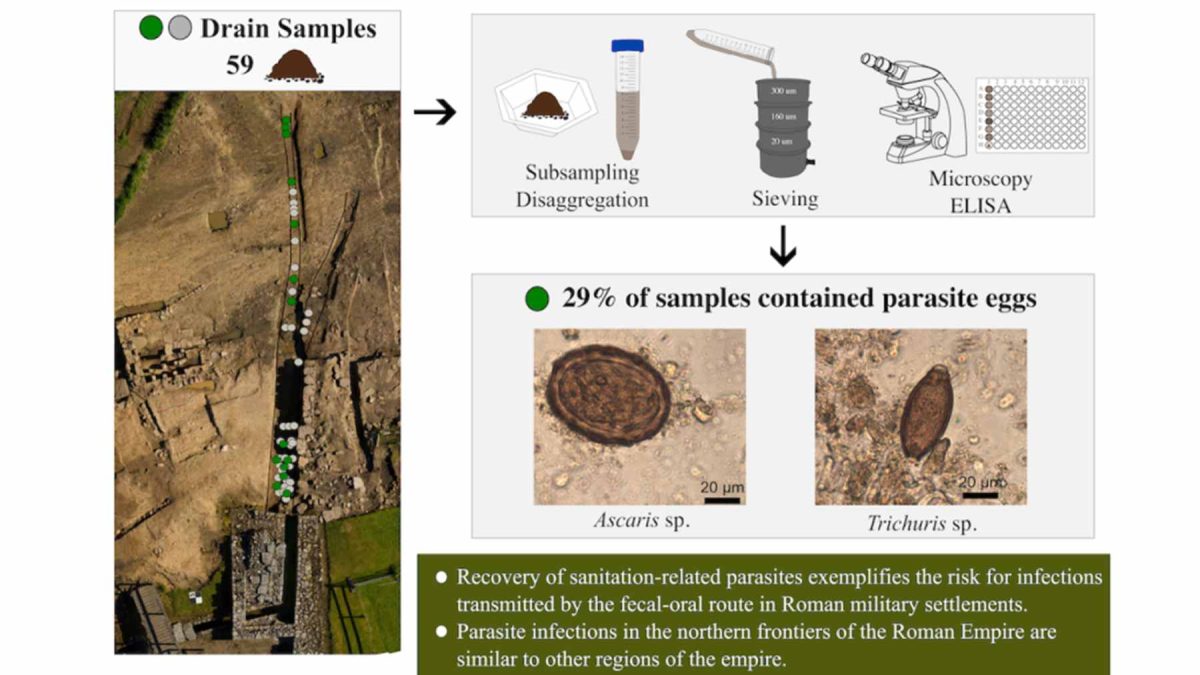

The Vindolanda drain samples report worm eggs in 28% and a diarrhea-causing parasite new to Roman Britain, plus traces in a ditch. Results point to daily sanitation limits for Roman troops at Vindolanda, just south of Hadrian’s Wall in northern England.

Sewers as biological records

Stone drains can preserve clues for archaeoparasitology, the study of ancient parasites in waste, long after flesh disappears. The work was led by Dr. Marissa L. Ledger at the University of Cambridge, where she tracks parasites in ancient sediments.

Her fieldwork turns forgotten waste into usable data, and it helps connect illness to daily life on the frontier.

A latrine drain in stone

At Vindolanda, a communal latrine, a shared toilet used by many, emptied into a stone drain beside the baths. The channel stretched about 30 feet and carried waste to a stream, building up layers during the third century A.D.

Feces settle unevenly in moving water, so collecting 50 samples along the drain reduces the chance of missing infection.

How eggs survive time

Waterlogged soil creates anaerobic, low-oxygen conditions that slow decay, letting parasite eggs persist in drains for centuries. Researchers rehydrated and sieved the sediment so heavy grit dropped away, and microscopes could spot preserved eggs.

Egg shape can identify a parasite group, but related species often look similar, so exact labels stay uncertain.

Roundworm and whipworm signals

Many positive drain samples contained roundworm or whipworm, parasites that spread when food or hands pick up human feces. These soil-transmitted helminths, intestinal worms spread through contaminated soil, reach new hosts when people swallow microscopic eggs.

Larvae mature inside the intestine and steal nutrients, so long infections can leave people tired and underfed.

Testing for hidden protozoa

Microscopes can miss some single-celled parasites, so the team also checked for biochemical fingerprints left in waste.

One method, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, a test that detects specific parasite proteins, can flag infection even after cells break apart. Because proteins decay faster than eggs, researchers treat positive signals as strong clues while keeping uncertainty in mind.

What Giardia does inside

Unlike worms, Giardia duodenalis, a gut parasite that causes diarrhea, spreads through contaminated water, food, and hands.

After entering the small intestine, the organism sheds its outer shell, multiplies, and starts taking nutrients from its host. In a crowded fort, a few contaminated cups or fingertips can pass the infection between many people in days.

The fecal-oral pathway

Poor hygiene feeds the fecal-oral route, germs moving from feces into mouths, even when a settlement has latrines. Shared seats, rinsing water, and unwashed hands can carry eggs or microbes onto food, then into someone else’s gut.

Direct spread becomes more likely in barracks or bathhouses where many people touch the same surfaces each day.

A frontier fort with families

Vindolanda sat on a hard northern frontier, and it housed soldiers beside traders, children, and other long-term residents.

Waterlogged deposits preserved writing tablets and leather shoes, giving a rare record of messages, supplies, and routine tasks. That unusually detailed setting makes health traces in waste more meaningful because they match a community we can describe.

When water becomes a vector

Drinking water can become a vector, a carrier that spreads germs between hosts, when sewage mixes with springs or pipes. Even if a drain aimed waste at a stream, rain and runoff could wash contamination back toward cooking and drinking areas.

Once the same water serves a bath, a bucket, and a cup, one tainted source can affect many users.

What the numbers cannot prove

Numbers from a drain cannot show how many people had symptoms, because eggs and microbes accumulate over long periods.

Some worms are zoonotic, able to spread between animals and humans, so nearby livestock could have added eggs to the drain.

Researchers treat the drain samples as community exposure, not a medical chart that pinpoints infection in each person.

Illness and readiness for duty

Chronic gut infections can weaken bodies by reducing nutrient uptake, and repeated diarrhea can dehydrate people during active work.

“These chronic infections likely weakened soldiers, reducing fitness for duty”, said Ledger.

A small drop in strength across a unit can matter when patrols, repairs, and training all depend on steady energy.

Drains also reveal design

Long stone drains do not move waste evenly, and a small change in slope can redirect where solids settle. Sampling along the full length can show which branch carried most material, because eggs appear more often where flow slows.

Archaeologists can use that pattern to map sanitation routes, but gaps in sampling can still hide short-lived pulses.

Why ancient sewage matters

Ancient sewers help track infections that rarely leave marks on bones, especially pathogens, germs that can cause disease.

This kind of evidence also shows how crowded living and limited hygiene kept feces-borne problems alive, even with Roman engineering. Modern plumbing breaks that chain by separating waste from water, yet the old patterns still echo wherever sanitation fails.

What comes from this

Taken together, the drain samples show how a well-built frontier fort still struggled against simple biology and shared surfaces.

Future work can test more drains and ditches, setting clearer limits on who was infected, when, and why outbreaks grew.

The study is published in Parasitology.