For millions of people, the day never really goes quiet. Even in a dark bedroom, with the phone on silent and the TV off, there is still that piercing ring or hiss in the background.

New work from neuroscientists at University of Oxford and collaborators in China suggests that this constant noise is tightly linked to one of the body’s most basic functions, sleep, and that deep sleep might temporarily turn the volume down.

Tinnitus is what scientists call a phantom perception, a sound that feels real even though no external source exists. Large studies estimate that roughly one in seven adults worldwide live with some form of it, with prevalence climbing in older age.

For many, the ringing gets worse at night, just when they are trying to wind down after a long day. The new data suggest that this is not a coincidence.

A phantom sound that competes with sleep

In 2022, a team led by neuroscientist Linus Milinski at Oxford’s Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute pulled together what was then scattered evidence on tinnitus and sleep. Their review in Brain Communications argued that tinnitus is not only a hearing issue.

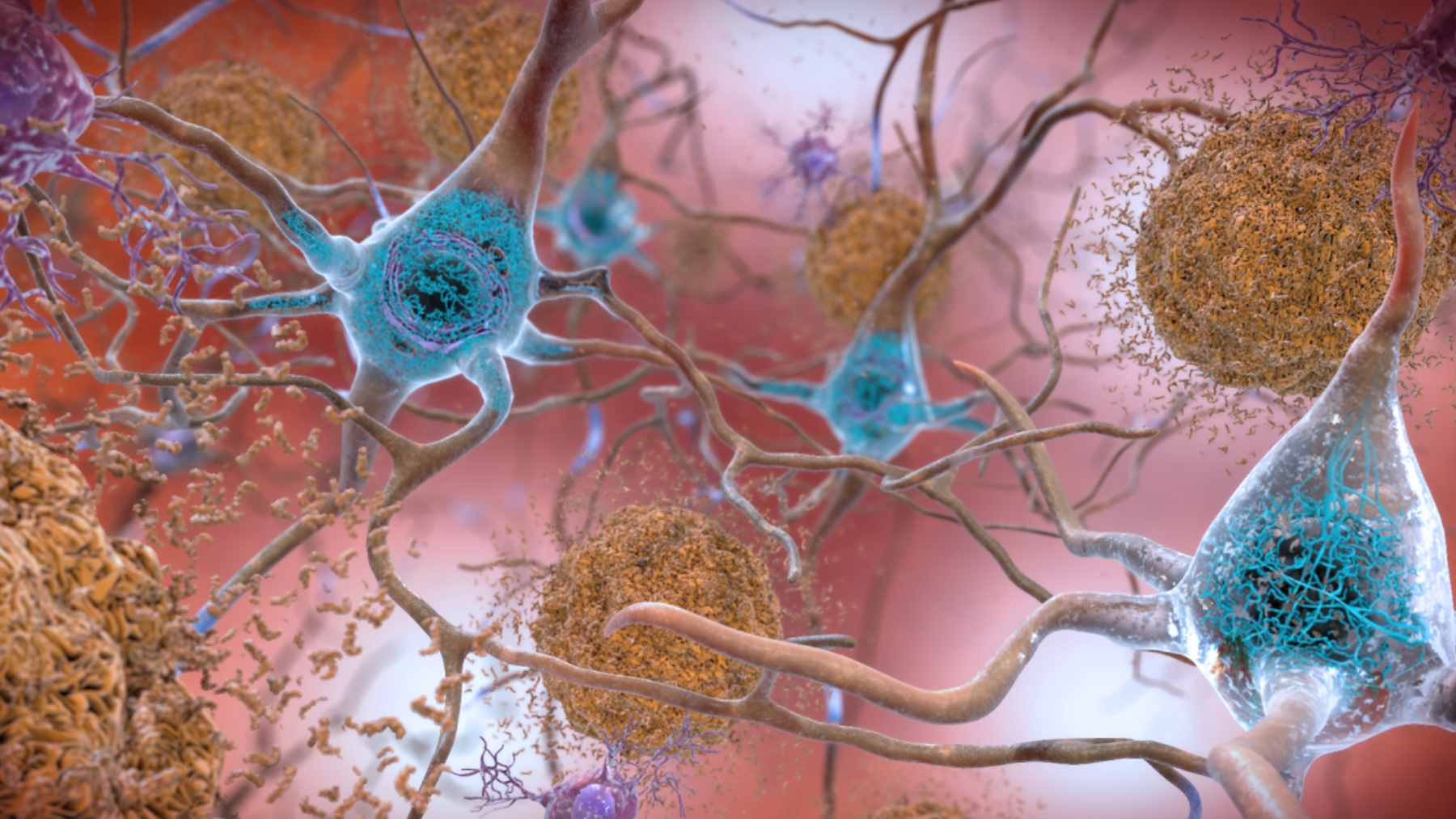

It also reflects abnormal brain activity that overlaps with circuits the brain uses to switch between wakefulness and deep non-REM sleep.

They proposed an idea that feels intuitive to anyone who has lain awake listening to their own ears. When tinnitus related activity stays high, it may keep parts of the brain in a state of local wakefulness, making it harder to reach truly restorative sleep.

At the same time, the powerful slow waves that dominate deep sleep might be able to override that faulty activity for a while and soften the phantom sound.

Ferrets show sleep can dampen tinnitus signals

Hypotheses are one thing. To test them, Milinski and colleagues turned to an animal whose hearing system looks a lot like ours, the ferret. In a 2024 study in PLOS ONE, they exposed eight adult ferrets to mild noise trauma and used behavioral tests to identify which animals developed signs of tinnitus.

The results painted a clear pattern. Ferrets that showed the strongest signs of tinnitus also developed more fragmented and shallow sleep. Their brains became unusually sensitive to sound when awake, a kind of hyperactivity that is thought to underlie phantom ringing in humans. Yet something interesting happened once those same animals finally dropped into non-REM sleep.

Neural markers of tinnitus in their brain recordings faded, even though the underlying hearing damage had not healed.

That suggests deep sleep is not just a passive break from the day. In these animals it acted more like a protective filter, temporarily masking tinnitus-related activity by engaging powerful slow wave networks across the cortex.

Human brains reveal a full day and night loop

Animal studies always come with limits, so researchers in China asked whether a similar story shows up in people. In 2025, a team led by Xiaoyu Bao at the South China University of Technology recorded detailed brain wave data from 51 adults with chronic tinnitus and 51 matched controls while they were awake and through their first sleep cycle.

They found what they described as persistent hyperarousal. Even with eyes closed at rest, tinnitus patients showed stronger fast brain activity in the gamma and beta ranges compared with people without tinnitus.

That fast activity did not switch off once they fell asleep. Across light sleep, deep sleep, and rapid eye movement sleep, the tinnitus group kept more high frequency activity and showed weaker slow waves, the very patterns that normally mark deep, restorative sleep.

In practical terms, their brains had a harder time settling into the kind of deep sleep that helps reset circuits after a noisy day.

The authors argue that this loss of slow, synchronized activity may stop the brain from fully dampening hyperactive auditory networks. Their conclusion is that tinnitus behaves less like an isolated ear symptom and more like a 24-hour brain state that stretches from daytime into the night.

A vicious circle that may still be breakable

People with tinnitus often report that poor sleep makes the ringing feel louder and more intrusive the next day. The new findings help explain why that everyday observation keeps coming up in clinics.

If the brain never quite reaches deep, slow wave sleep, tinnitus-related activity has more room to run. At the same time, the constant phantom sound makes it harder to drift off in the first place.

That is a rough loop for anyone, and especially for older adults who may already be dealing with hearing loss, social isolation, or anxiety. Chronic stress is known to worsen both sleep and tinnitus for many patients, so nights of tossing and turning can quickly spill into mood problems and daytime fatigue.

Researchers are now asking whether sleep itself could become a direct treatment target. That might mean carefully-designed behavioral therapies to improve sleep quality, new ways to time sound-based therapies to the sleep cycle, or even future drugs that nudge the brain into deeper slow wave activity without side effects.

For most people with tinnitus, there is still no quick fix, but sleep science is starting to offer a different way to think about the problem.

The most recent study was published in Sleep Medicine.