Starting March 1, one of the most affordable lifelines for small businesses with immigrant owners will sharply narrow. Under a new rule from the U.S. Small Business Administration, companies with any ownership by non‑citizens, including green card holders, will no longer qualify for the agency’s flagship 7(a) and 504 loan programs.

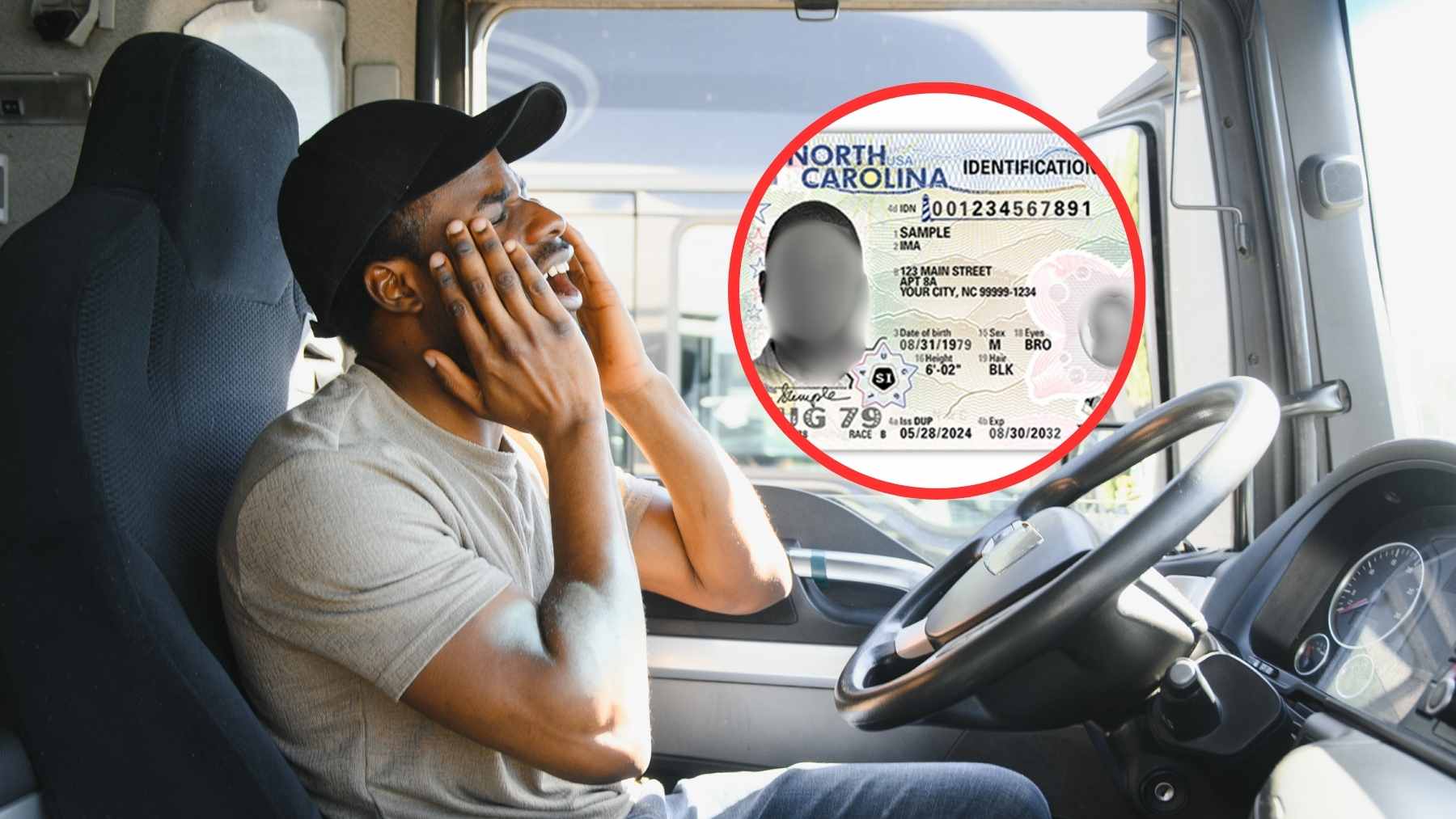

For many entrepreneurs who run neighborhood restaurants, corner stores, or small trucking fleets, SBA‑backed loans often mean the difference between opening the doors and watching a business plan die on paper.

These loans do not come directly from Washington. Instead, the SBA guarantees bank loans so lenders can offer lower rates and longer repayment terms than typical commercial loans, which helps owners cover rent, payroll, and that never‑ending stack of utility bills.

What exactly is changing

Until recently, SBA rules required that at least 51% of a borrower be owned by U.S. citizens, nationals, or lawful permanent residents. In 2025 the agency moved to a stricter standard that called for full ownership by those groups.

Then, in December, a narrow exception briefly allowed up to 5% ownership by foreign nationals or permanent residents who lived abroad. The newest guidance rescinds that exception and removes lawful permanent residents from eligibility entirely, so every direct and indirect owner must now be a U.S. citizen or national who primarily lives in the country.

Officials tie the change to President Donald Trump and his broader immigration agenda. An earlier policy notice cites an executive order titled “Protecting the American People Against Invasion,” which directed agencies to tighten access to taxpayer-funded benefits for people who are not citizens.

SBA spokesperson Maggie Clemmons has said the agency will “no longer guarantee loans for small businesses owned by foreign nationals” and argues that every federal dollar should go toward U.S. job creators.

Immigrant entrepreneurs on the line

Immigrant advocates and many lawmakers see the same rule through a very different lens. Senator Ed Markey and Representative Nydia Velázquez, who lead the Democratic minority on the Senate and House small business committees, warn that tougher citizenship checks and higher loan fees have already dragged down SBA lending.

Blocking green card holders completely, they argue, will land hardest on Main Street.

Their concern is backed by data. Immigrants own nearly one fifth of employer firms in the United States and close to one quarter of non‑employer businesses, according to tabulations from the Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey and the SBA Office of Advocacy.

Those businesses are not an edge case. They are the grocery on your block, the warehouse down by the highway, the rideshare fleet that keeps commuters moving.

Researchers and advocacy groups have also noted that immigrants start businesses at roughly twice the rate of U.S.-born residents.

Small business network leaders like the Small Business Majority say the new SBA rule will “limit the growth of small businesses and jobs throughout the United States,” since many of those high‑propensity entrepreneurs will lose access to the most affordable credit on the market.

What happens next for small businesses

For lawful permanent residents who already have an SBA loan, there is one small bit of reassurance. Existing loans are not being yanked away. The new standard applies to fresh applications and to future ownership changes.

If a current borrower brings in a new partner after March 1, that partner will need to be a citizen or national to keep the loan in good standing.

The immediate crunch falls on entrepreneurs in the middle of the process. Applications that involve any ownership by green card holders need to be fully approved before the rule takes effect. Otherwise, owners will have to rearrange their cap tables so citizens hold every share, or look to costlier online lenders and commercial banks that do not have federal guarantees behind them.

Supporters of the Trump policy say steering government-backed credit only toward citizen-owned firms respects taxpayers and keeps the focus on domestic hiring. Critics counter that it treats lawful permanent residents like second-tier participants in the economy, even though they pay taxes, employ workers, and often hope to become citizens themselves.

At the end of the day, the fight over this rule is really a fight over who gets to stand at the front of the line when a local bank decides which dreams to fund.

The official statement was published by the U.S. Small Business Administration.