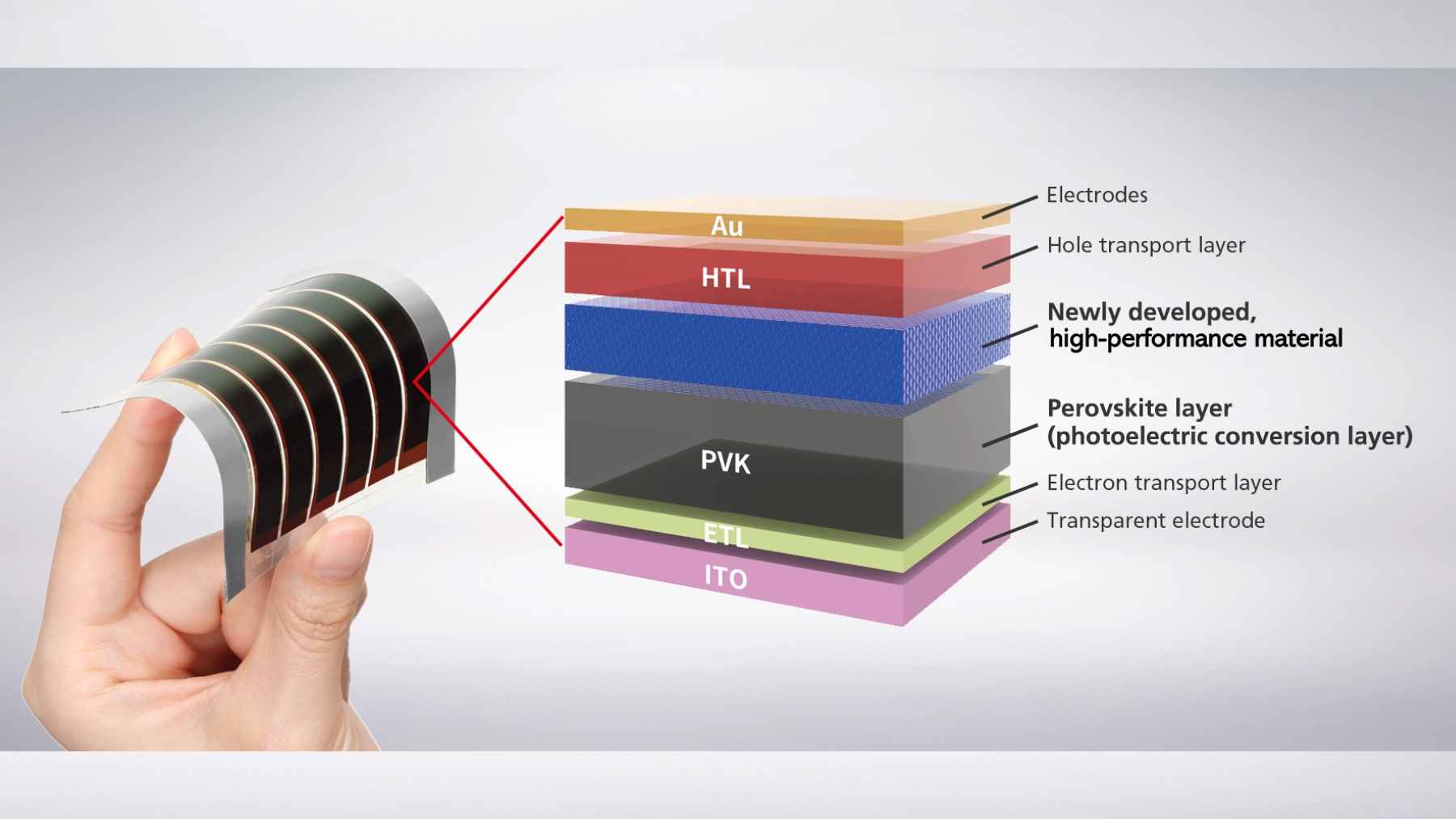

Perovskite solar cells have long been billed as the next big thing in clean energy, promising thin, flexible panels that sip raw materials yet rival the best silicon in efficiency. In the lab, these perovskite solar cells now reach efficiencies in the mid-twenties and even higher according to independent test labs.

The catch is stability. Out in the real world, sunlight, air, and heat can quietly tear the material apart long before a typical rooftop system would pay for itself.

Why perovskite solar cells degrade in air and sunlight

So what is actually going wrong inside these cells? Researchers have shown that the perovskite crystal is highly sensitive to environmental stress, especially a mix of moisture, heat, light, and oxygen that can accelerate decomposition over time, a problem reviewed in detail for commercialization efforts in perovskite solar cells.

Under strong illumination, metal oxide layers in the device help create very energetic electrons. When oxygen is present, those electrons can turn it into superoxide, a particularly reactive form that attacks the perovskite and triggers fast degradation.

It is the materials science equivalent of rust forming where you least want it. Similar photo driven reactions that destroy materials at room temperature are already a hot topic in other branches of chemistry.

Octopus inspired taurine layer could boost perovskite solar cell durability

A team in South Korea decided to borrow a trick from marine life rather than just tweaking industrial coatings again.

Scientists at the Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology and the Korea Institute of Science and Technology asked a simple question. If octopuses and squid spend their lives in salty, oxygen-rich water bathed in sunlight, what keeps their cells from being chewed up by the same kind of reactive chemistry.

Their attention turned to taurine, an amino acid that sea creatures and humans use as a kind of built-in shield against oxidative stress. Reviews of taurine in biology describe it as a natural antioxidant that helps mop up reactive oxygen and protect tissues.

The Korean group took that same molecule and slipped a layer of it between the tin dioxide electron transport layer and the perovskite absorber inside their test cells.

Interface engineering to reduce superoxide damage and improve performance

In practical terms, that thin taurine layer acts as a chemical sponge. The study describes how superoxide radicals formed at the metal oxide interface are quenched before they can dig into the perovskite, while the molecule’s charged groups also help tie the tin dioxide and the crystal together more cleanly.

The result is a buried interface with fewer defects, better charge flow, and much slower structural damage during harsh light and oxygen exposure.

Devices built this way not only perform better electrically, they hold on to their performance longer under aggressive stress tests, which is exactly the kind of behavior long-term field systems need.

What longer-lasting perovskite solar panels could mean for real-world energy

Seen from a distance, the work is part of a broader pattern. Scientists are increasingly raiding biology for ideas, whether that means learning from unexpected discoveries of new species on remote islands or rethinking how dust on the Moon records the history of our solar system.

Here, an everyday molecule best known from physiology and energy drinks quietly becomes a bridge between marine biology and solar engineering.

If approaches like this scale, they could help perovskite panels move from short-lived lab curiosities to real products that sit on rooftops for decades, cutting both electricity bills and the noise and pollution from older fossil fuel infrastructure that cities are already trying to curb with measures such as bans on gasoline powered tools.

There is still a long road from a carefully built cell in a controlled lab to mass produced modules on homes and warehouses. Yet the idea that a molecule borrowed from an octopus can make cutting-edge solar technology tougher is a reminder that nature’s toolbox is often broader than it looks at first glance.

The study was published in Advanced Energy Materials.