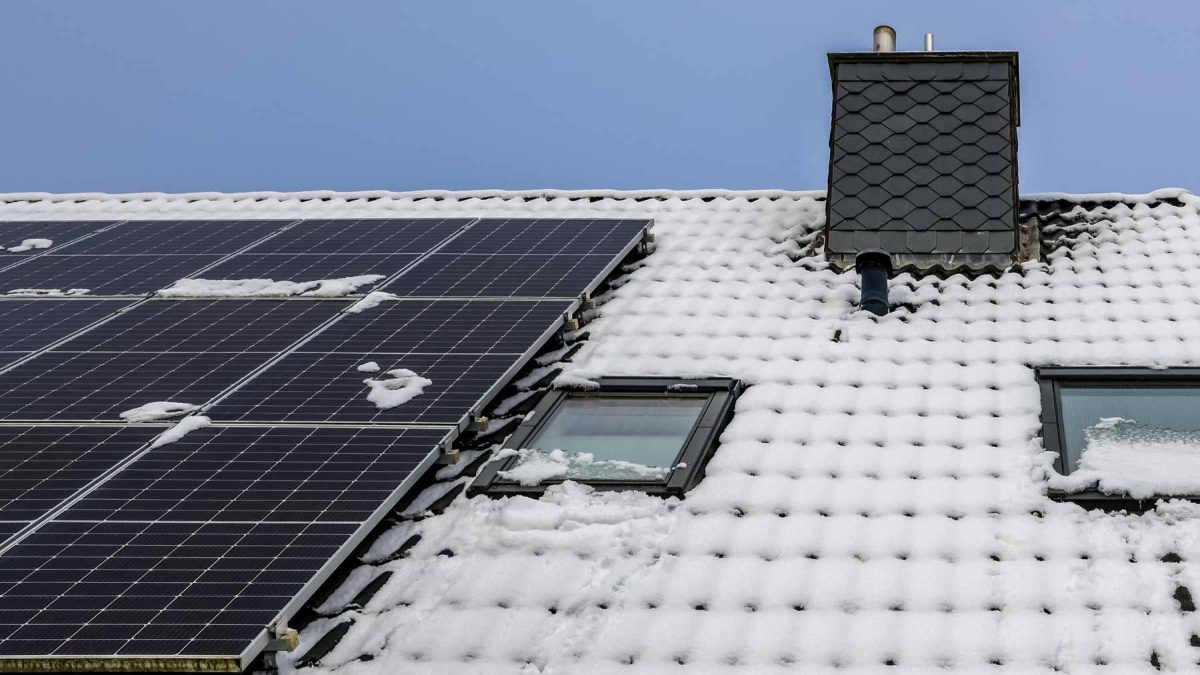

When the first snow of the season starts dusting roofs, cars, and backyards, a lot of people with rooftop solar have the same thought. If the panels are white instead of blue, are they even working?

New field data and fresh scientific reviews suggest the answer is more interesting than it looks from the sidewalk. In cold, snowy weather, solar panels can sometimes perform better than many homeowners expect, and in a few setups they even gain a boost from the snow around them.

Why cold air can be good news for solar

Solar photovoltaic cells are electronic devices. Just like a laptop that runs hotter and slower when it is working hard, solar modules lose some efficiency as they heat up. In winter, the air is colder and panels tend to run cooler. That helps keep voltage higher and reduces internal resistance.

A recent review in the journal Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews finds that as panel temperature rises, efficiency typically drops by about 0.4 to 0.5 percentage points per degree Celsius. In other words, a panel baking on a summer roof may give up several percent of its output simply because it is hot, while the same module on a crisp winter day keeps more of the sunlight it captures.

Researchers writing about long-term performance in cold and snowy regions also report that photovoltaic systems often degrade more slowly there than in hot desert climates, drawing on long-term performance in cold and snowy regions. Their data suggest that modern modules can handle freeze-thaw cycles, ice loads, and wind gusts without the rapid wear that many people worry about, as long as they are installed to code and maintained.

The mirror effect of fresh snow

That still leaves the obvious question. If snow is sitting on the glass, how can light get through?

Fresh snow is extremely bright. Light colored surfaces like new snow can reflect up to 80 percent of incoming sunlight, an effect that engineers call the albedo effect. When the sun hits a white field or a nearby roof, some of that light bounces onto any exposed parts of a panel.

In open landscapes or on steeply tilted arrays, that reflected light can add a small but real boost to winter energy production.

High-altitude solar installations like the AlpineSolar project on Switzerland’s Muttsee dam show how snow, cold air, and a steep tilt can deliver strong winter production.

Panels high in the Alps sit over the fog, catch low winter sunlight, and benefit from reflected radiation off white slopes. In practical terms, that means more electricity in the very season when heaters, trains, and factories are hungry for power.

Snow as a natural cleaner

Of course, snow can still block light if it piles up thick and stays put. That is why system design matters.

One recent scientific review of snow impacts describes how even modest tilt and smooth glass help snow slide as soon as the sun warms the surface a little. Gravity does much of the work. When the snow sheet releases, it often drags dust and pollen that have built up on the panel, leaving the surface cleaner than it was before the storm.

At the end of the day, that “self cleaning” effect is one reason long-term studies in cold regions do not see winter as a disaster for solar. For most of the year, the glass stays clear. When snow does arrive, it tends to stick for a limited time, then slide off and leave a freshly-washed surface behind.

The role of test sites and real-world data

For homeowners and businesses, the reassuring part is that most of these conclusions come from full-scale systems, not just lab experiments.

At a Regional Test Center in Vermont, researchers funded by the U.S. Department of Energy tracked photovoltaic arrays through multiple winters.

Their measurements showed that light snowfalls barely dented annual production, and even heavier storms translated into only a few percent loss over the course of a year. Tilt angle, local weather, and shading turned out to matter more than the simple fact that it snows.

A five-year study in Edmonton told a similar story. Engineers there found that accumulated snow cut annual energy output by only a few percent, far less than the 20 percent penalty that installers once assumed. For customers, that difference can be the line between a scary “what if” and a comfortable electric bill.

A broader scientific review of environmental effects of utility scale solar adds an important nuance. Snow, dust, and pollen are part of a larger picture that includes land use, habitat changes, and material sourcing for panels. When researchers add everything up, they still find that solar power tends to have much lower lifetime emissions and health costs than fossil fuel generation, even in northern climates.

What it means for your rooftop (and your winter bills)

For most households, the practical takeaway is simple. A properly installed solar array will keep generating through winter. Output on short, cloudy days will dip a bit, but cold air and occasional mirror-like snow around the panels help offset some of that loss.

Energy agencies and engineers generally do not recommend climbing onto the roof to sweep snow unless safety and structure are at risk. The risk of a fall or damage usually outweighs the small extra energy you might gain. Instead, they focus on getting the tilt and layout right at installation, so gravity and sunshine handle most winter cleanup.

As climate patterns shift, snow cover in many regions is changing, but the core physics remain the same. Solar cells like cool temperatures, and reflective snow can be a quiet ally rather than an enemy, especially on tilted, unobstructed arrays. That basic physics holds even as scientists keep a wary eye on the long-term future of our planet and the Sun itself.

The study was published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews.