Every time you flip on a light, you are tapping into a technology that goes back to the Menlo Park workshop of Thomas Edison. Now a new study suggests those early carbon-filament bulbs may have produced graphene, a material not formally isolated until the early 2000s.

What is graphene?

Graphene is a sheet of carbon just one atom thick. It is remarkably strong and light, conducts electricity extremely well, and appears in research on flexible screens, faster batteries, and advanced sensors.

Physicists Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov finally isolated it in 2004, work that later earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Rice University recreates Edison’s light bulb experiment

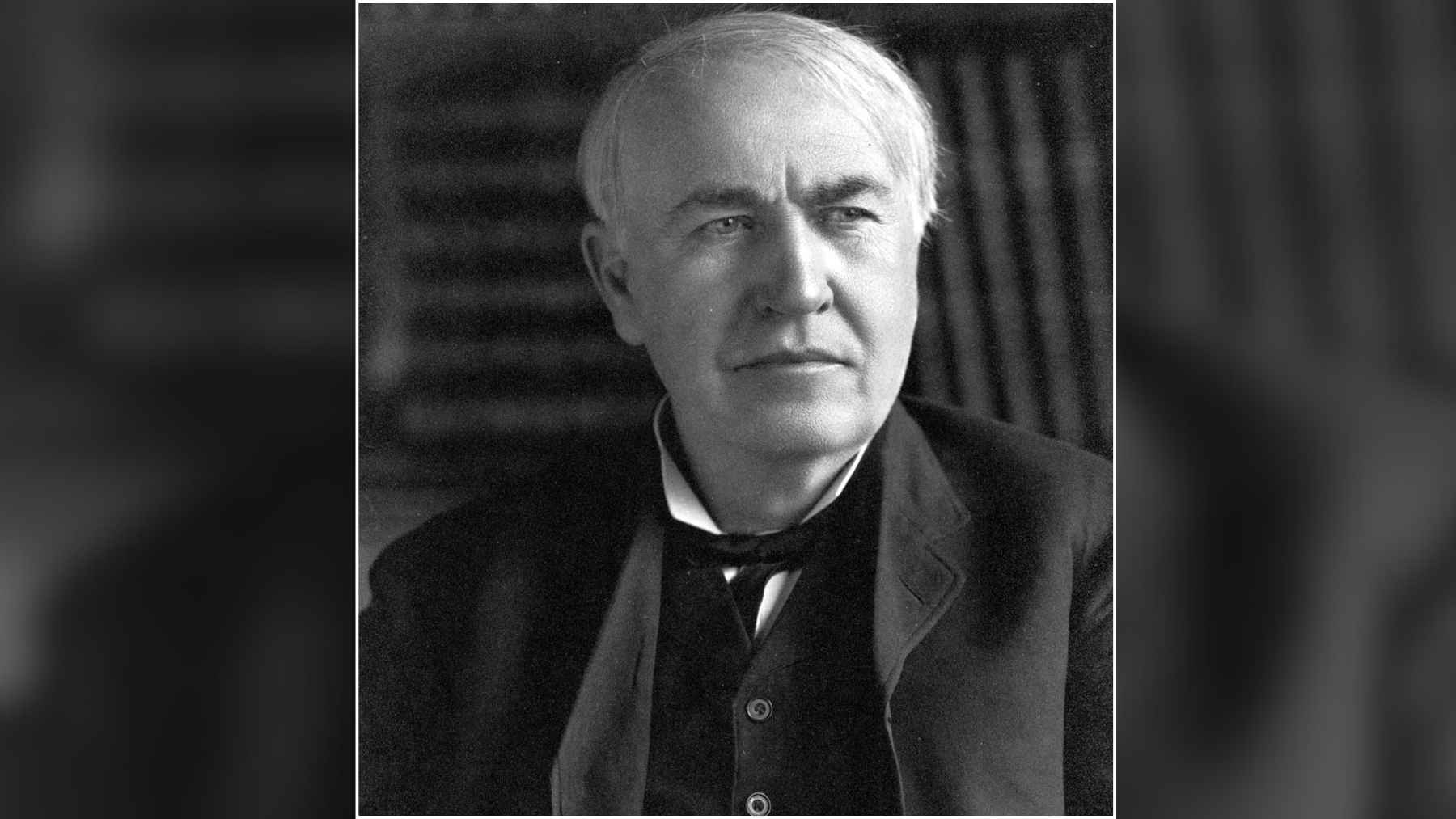

The new work, led by chemist James Tour and first author Lucas Eddy at Rice University, set out to recreate Edison’s 1879 light bulb as faithfully as possible. The team dug into Edison’s patent, then tracked down artisan bulbs with carbonized Japanese bamboo filaments instead of the tungsten wires in modern lamps.

With the bulbs in hand, the researchers wired them to a 110 volt direct current supply, just as Edison did. Each bulb was switched on for only about twenty seconds because longer runs tend to turn carbon into ordinary graphite.

Even in that short burst, the filament changed, and under an optical microscope sections that had started out dull gray took on a bright, silvery sheen.

Detecting turbostratic graphene in antique filaments

To find out what had happened, the team used Raman spectroscopy, a laser-based technique that reads the “barcode” of a material.

The spectra matched what scientists expect from turbostratic graphene, a form in which several graphene layers sit loosely stacked and slightly misaligned instead of being locked into perfect order.

That structure can make graphene easier to mix into composite plastics or other devices.

In practical terms, Edison’s bulb was behaving like a very simple version of flash Joule heating, a modern method for making graphene by sending intense pulses of current through carbon-based materials until they reach more than two thousand degrees Celsius.

For Edison, those extreme temperatures were simply the cost of building a bright, long-lasting lamp that could replace gas flames in homes and streets.

Did Thomas Edison really invent graphene?

So does this mean Edison “invented” graphene a century early? Not quite. The Rice team stresses that they cannot test his actual bulbs, and any graphene that formed during long burn in trials would probably have converted to graphite.

Edison had no way to see nanoscopic sheets forming for a few moments inside his vacuum bulbs, and no reason to scrape them off for study.

Hidden breakthroughs in historical experiments

What the study does show is that advanced materials science sometimes appears in history before scientists have the tools to describe it.

A graduate student searching for cheaper ways to make graphene found inspiration in an antique light bulb that once hung over everyday workspaces. As James Tour put it, reproducing Edison’s work with modern tools is exciting because it hints at “what other information lies buried in historical experiments.”

For the rest of us, the idea that a 19th-century light bulb could briefly host one of today’s “wonder materials” is a reminder that familiar technologies can hide extreme physics and chemistry behind their warm glow.

The next time you look at a glowing filament, you might picture carbon atoms lining up, just for a heartbeat, into something that belongs to the 21st century.

The study was published in ACS Nano.