Technology in orbit has just confirmed something sailors have whispered about for generations. In December 2024, a powerful North Pacific storm created waves that rose to around 35 meters in deep water, roughly the height of an eleven-story building, and satellites saw them clearly for the first time.

Scientists say these are the largest open ocean waves ever measured from space and that the data could change how we prepare for danger at sea. What does a wave that size really mean in practice?

The extreme episode came from Storm Eddie, an intense weather system over the North Pacific between Hawaii and the Aleutian Islands. As the storm peaked on December 21, the French United States SWOT satellite measured average wave heights near 20 meters while individual crests likely pushed past the 35 meter mark. For any ship in the wrong place, those crests would look and feel like fast-moving walls of water.

How satellites learned to read the sea surface

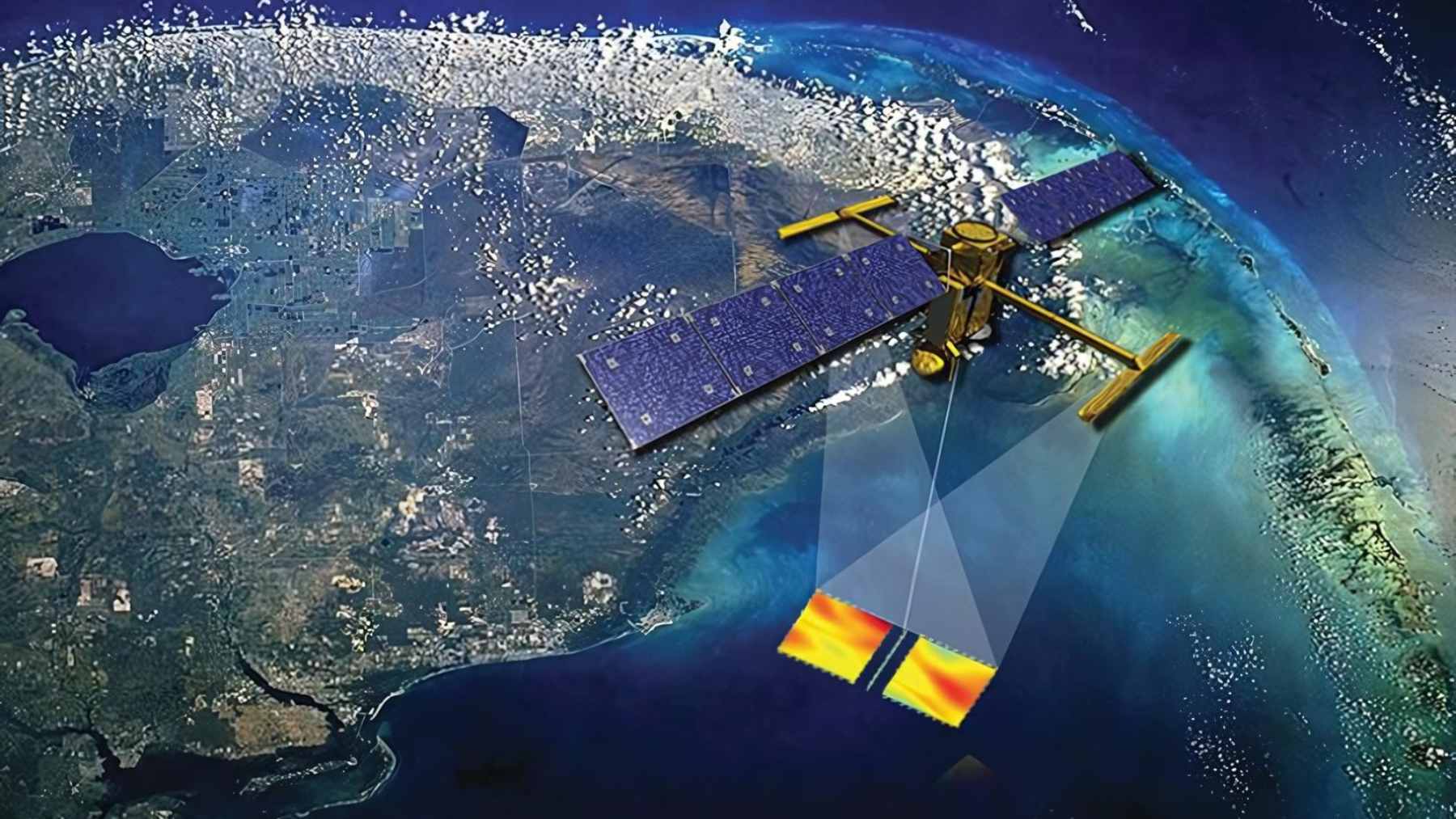

For a long time, stories of such waves came mainly from damaged ships, offshore platforms, and a handful of buoys. Now a fleet of ocean-observing satellites measures the height of the sea surface by sending radar pulses down and timing how quickly the signal returns. SWOT adds wide-swath imaging, so scientists can map a broad ribbon of ocean on every pass and spot sudden peaks that would slip past traditional instruments.

In this new work, researchers paired SWOT measurements with more than three decades of ESA Climate Change Initiative Sea State records from missions such as SARAL, Jason 3, Sentinel 3, Sentinel 6, CryoSat, and CFOSAT. That combined record, which stretches back to 1991, now captures the most extreme waves in the open ocean instead of only the ones that happen to hit a buoy or ship.

Storm energy that circles the globe

The same swell that produced the 35 meter crests near the heart of Storm Eddie did not stay there. Scientists tracked its signature for about 24,000 kilometers, from the North Pacific through the Drake Passage and into the tropical Atlantic between late December 2024 and early January 2025. Those waves helped power the legendary Eddie Aikau big wave contest in Hawaii and record breaking sessions at the surf break known as Mavericks in California.

In practical terms, that means a storm that never touches land can still send serious energy into far-off coastlines. Long period swells reach beaches thousands of kilometers away, raising the baseline for high tide and quietly chewing at dunes, cliffs, ports, and coastal defenses that already work harder in a warmer, higher ocean.

New numbers for shipping and offshore energy

For ship operators, knowing that a remote storm can build 30-to-35-meter waves is not just a curiosity. It shapes routing, insurance, and the rules that keep crews and cargo safe. The same data matter for offshore platforms and wind farms that help shrink the carbon footprint of the electric bill, and the analysis suggests older models underestimated how much energy sits in the dominant waves instead of the longest swells.

What this says abouta changing climate

By tying satellite observations to computer models, scientists can now track how the strongest storms behave and how often they appear. Fabrice Ardhuin notes that “climate change may be a driver, but it is not the only one” and stresses that seafloor shape and the rarity of such events still matter.

Rather than blaming Storm Eddie on climate change, the work gives researchers tools to test long-term trends and refine forecasts for coasts facing rising seas and stronger storm seasons.

At the end of the day, the message from orbit is simple. The open ocean is wilder than we thought, even on days when the satellite images look like a smooth blue sheet. Turning those hidden waves into solid numbers is one way to give ships, coasts, and ecosystems a fighting chance as the climate era unfolds.

The study was published in the journal PNAS.