A new gene-edited fungus developed in China is being pitched as a double win for dinner plates and the climate.

The strain, called FCPD, delivers protein with a meatlike taste and texture while using 44% less sugar, cutting production time by 88%, and lowering greenhouse gas emissions by up to about 60% compared with standard fungal protein production.

At a time when the world is heading toward nearly ten billion people by mid-century and livestock already accounts for roughly 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions, the appeal is obvious.

Growing enough beef and chicken means vast fields for feed, heavy water use, and, in many regions, the kind of heat wave summers that make air conditioners and electric bills work overtime. A protein source that behaves like meat but sidesteps much of that footprint is going to draw attention.

A meatlike fungus built with CRISPR

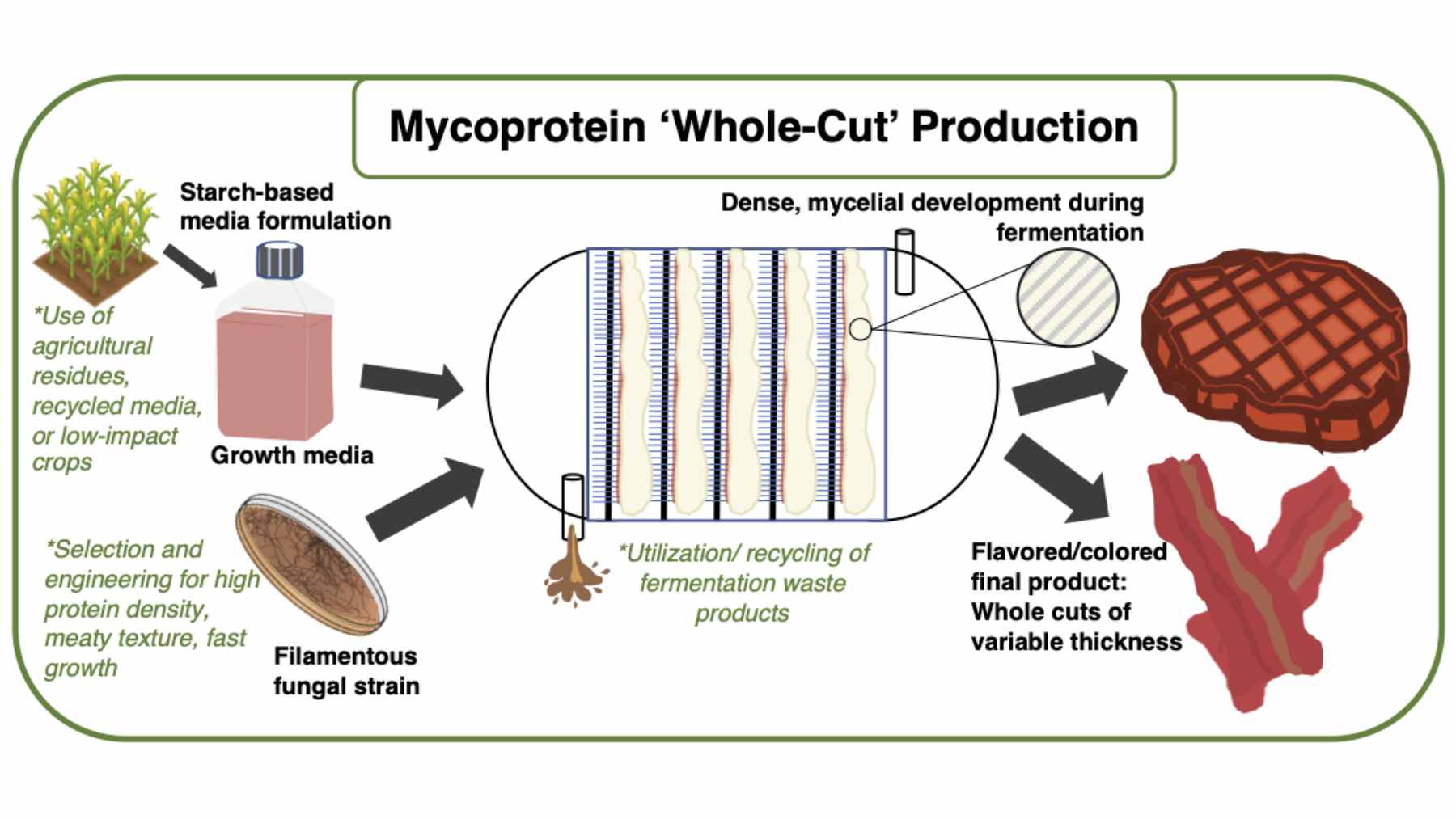

The work comes from researchers at Jiangnan University, who started with Fusarium venenatum, the filamentous fungus already used as mycoprotein in products sold under brands such as Quorn.

This species naturally forms fibrous strands that cook and chew a bit like poultry, which is why it has become a favorite base for plant-based nuggets and patties.

There was a catch. Traditional Fusarium venenatum has thick cell walls rich in chitin that make its protein harder for the human body to fully digest, and cultivating it at scale soaks up large quantities of sugar and electricity.

The Jiangnan team used the CRISPR gene editing tool to knock out two specific genes. One controls chitin synthase, so removing it thins the cell wall and exposes more of the protein. The other encodes pyruvate decarboxylase, a key enzyme in metabolism, and disabling it nudges the fungus to use nutrients more efficiently.

Crucially, the edits did not add foreign DNA. The researchers describe FCPD as a scarless gene-edited strain rather than a classic transgenic GMO. That detail will matter in future regulatory debates and supermarket conversations.

Cutting sugar, land, and emissions

Inside industrial tanks, FCPD behaves very differently from its parent strain. Tests showed it could produce the same amount of protein using 44% less sugar while reaching that output 88% faster.

The team then ran a full life-cycle assessment, tracking environmental impacts from lab spores all the way to inactivated meatlike products. They simulated production in six countries with very different energy mixes, from mostly renewable-heavy Finland to coal-reliant China.

In every scenario FCPD came out ahead of conventional Fusarium venenatum, cutting greenhouse gas emissions by up to about 60% across the system.

When they compared the fungus to animal agriculture, the gap widened. Against chicken production in China, FCPD mycoprotein required around 70% less land and reduced the risk of freshwater pollution by about 78%.

For anyone who has driven past a crowded poultry farm or worried about manure runoff into rivers, those numbers tell a pretty concrete story.

What it could mean for your plate

From a consumer point of view, two questions usually come first. Does it taste like real meat, and will my stomach handle it well? Early reports suggest FCPD offers a meatlike flavor while its thinner cell walls make the protein easier to digest than the wild strain it came from.

In practical terms that could mean future meat alternatives that feel less like compromise. Imagine grabbing a bag of strips or cutlets made from this fungus that sear, shred, and soak up sauce the way chicken does, without needing millions of birds, feed fields, or the associated emissions.

The study also indicates that FCPD compares favorably with other alternative proteins, including some forms of cultivated meat, on several environmental indicators.

Promise and questions ahead

For the most part, scientists see gene-edited foods like FCPD as one more tool in a broader push to clean up the food system rather than a magic bullet.

The technology can make existing microbes and crops work harder with fewer inputs, but it still relies on fermenters, electricity, and feedstocks such as sugar. Critics also point out that consumer trust around genetic technologies remains fragile in many countries, regardless of whether foreign DNA is involved.

Regulators will now have to decide how to classify and label products built from this strain, and whether gene-edited fungi should be treated differently from older GMO foods. Shoppers will make their own choices at the meat case and freezer aisle, just as they already weigh cage-free labels or plant-based milks.

What is clear is that protein grown in tanks rather than barns is no longer a distant thought experiment. It is becoming another option for cutting the climate and water impact of what ends up on the grill.

The study was published in Trends in Biotechnology.