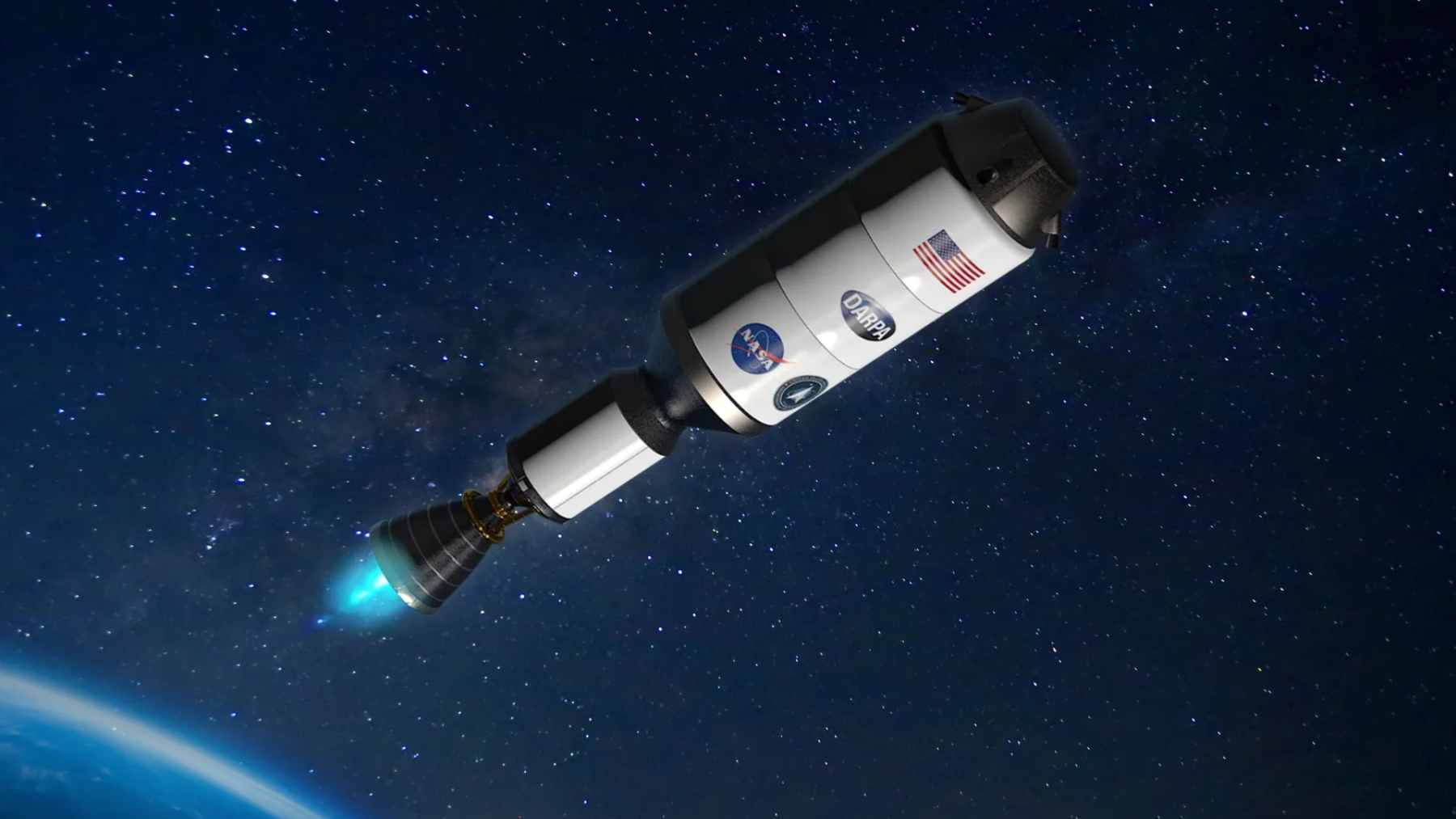

For the first time in more than half a century, NASA has put a flight-scale nuclear rocket reactor through a full series of ground tests, a quiet milestone that could one day turn months-long journeys to Mars into something much shorter.

Teams at Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama ran more than one hundred cold flow tests on an engineering development unit over several months in 2025. The hardware is a non-nuclear mockup about the size of a 100 gallon drum that simulates how super cold liquid hydrogen would snake through a real space reactor.

If chemical rockets are like trying to cross an ocean in a small boat, this work is aimed at building the equivalent of a fast ship. Same basic idea, very different range and comfort.

What NASA actually tested

The reactor unit, built by BWX Technologies, measures roughly 44 inches across and 72 inches tall. It is a full-scale, flight-like test article rather than a tiny lab sample.

Engineers pumped propellant through the maze of internal channels to mimic real operating conditions while keeping everything non radioactive. This cold flow campaign let them watch how the fluid behaved inside the reactor, map pressure changes, and check for any nasty surprises such as vibrations or oscillations that could shake a future engine apart.

According to NASA, the tests showed that the design is not prone to destructive flow induced shaking. That kind of stability matters because once you strap a reactor to a crewed spacecraft, you really do not want the plumbing to start humming itself to pieces halfway to Mars.

Jason Turpin, who manages NASA’s Space Nuclear Propulsion Office at Marshall, explained that the team did much more than flip a switch and collect a few numbers.

He said the campaign produced some of the most detailed flow response data seen for a space reactor design in more than fifty years and called it a key stepping stone toward a flight-capable system.

Why nuclear propulsion matters for future crews

So why go to all this trouble when conventional rockets already reach Mars and the outer planets? The answer sits in the way these engines use fuel.

Chemical rockets burn propellant, which limits both how fast a spacecraft can go and how much mass it can push. A nuclear thermal rocket instead uses a compact reactor to heat a light propellant such as hydrogen before it rushes out the nozzle.

In practical terms, that means a much higher exhaust speed and far better efficiency.

For a human mission to Mars, that extra performance could shave months off the trip. Shorter journeys translate into less time for astronauts to soak up cosmic radiation, fewer supplies to keep them alive, and crews who arrive less worn down by the long haul.

The same technology could let robotic probes carry more instruments and enjoy higher electrical power for communication and science gear, even far from the Sun.

Greg Stover, acting head of NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate, highlighted those benefits in the agency release.

He noted that nuclear propulsion offers both speed and endurance and argued that cutting travel times while boosting payload and power can lay the groundwork for exploring deeper into the solar system than current systems allow.

A long road from test stand to deep space

The new reactor unit is not yet tied to any specific mission. This is still technology development, not a finished engine bolted to a Mars ship. Cold flow tests like these are closer to checking all the pipes and valves in your home before you ever turn on the furnace.

Even so, they matter. The data feed directly into the design of flight instrumentation and control systems and help validate computer models that will guide future reactors from first ignition to shutdown.

At the end of the day, each successful run in that Alabama test stand quietly chips away at one of the biggest limits on deep space exploration. Faster trips, heavier science payloads, more capable missions far from the Sun all start with getting the engine right.

For now, the flight-like reactor remains bolted to steel supports rather than riding atop a rocket, and human voyages to the outer planets stay in the realm of plans and concept art.

The official press release was published by NASA.