The U.S. Navy is trying to rebuild its fleet in the middle of a deep shipbuilding crisis. New warships arrive late, cost more than promised and sometimes do less than planners hoped, even though the shipbuilding budget has nearly doubled over the last two decades and the total number of ships has not grown.

In recent testimony to Congress, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) warned that this pattern of cost growth, delivery delays and underperforming vessels is built into the way the Navy designs and buys ships. GAO concluded that without a fundamental reset the fleet will keep falling short just as maritime threats increase.

So why should people who care about oceans, coastal air quality and the climate pay attention to a debate about frigates and submarines? Because the same struggling industrial base that is missing military deadlines is also a powerful driver of pollution and energy use, and the choices made now will lock in shipyard emissions for decades.

A fleet in trouble

GAO’s latest reports describe a familiar pattern. Construction on some high-profile programs started before designs were mature, which goes against leading commercial practice and has already pushed the first Constellation class frigate at least three years behind schedule.

Earlier experiments such as the Littoral Combat Ship and Zumwalt class destroyer consumed tens of billions of dollars more than initially budgeted and still delivered fewer ships with less capability than promised. At the same time, private yards that build and repair Navy vessels face cramped sites, aging equipment and shortages of skilled workers, which have contributed to delays of up to three years on some programs.

The Navy and the Department of Defense have poured billions into expanding shipbuilding capacity and workforce programs. Yet GAO found that the services have not fully assessed whether those investments are working, and they continue to plan for fleet growth that exceeds what the industrial base has shown it can realistically deliver.

Meanwhile, political pressure to think big is rising. In December 2025, the Navy announced a new Trump class battleship as the centerpiece of a Golden Fleet, with the lead ship USS Defiant described as the most lethal surface combatant in history and roughly triple the size of a standard destroyer, while outside analyses warn that the program could cost tens of billions of dollars over time.

Shipyards as climate hotspots

Shipbuilding does not just shape naval strategy. It also shapes the air and water around coastal communities that live next door to the yards. Environmental assessments show that modern shipyards generate localized pollution in the form of heavy metals, volatile organic compounds from paints and coatings, large volumes of solid waste and significant energy demand concentrated near ports.

One recent life cycle study estimated that building the hull of a single Panamax oil tanker can produce around 14,500 tons of carbon dioxide, with roughly 90% of those emissions tied to steel fabrication alone.

Another case study of a 50 meter yacht found about 1,500 tons of carbon dioxide from manufacturing, again dominated by the hull and superstructure.

Those numbers sit on top of the broader climate footprint of iron and steel manufacturing, which researchers estimate accounts for roughly 4% to 5% of total human-produced carbon dioxide.

When navies order larger and more complex ships without demanding cleaner production, they indirectly lock in more emissions from some of the most carbon-intensive industrial processes on the planet.

Modern yards are also energy hungry. Cutting, welding and moving thousands of tons of steel all day long means high electricity and fuel use, which ultimately shows up in the same power system that feeds household electric bills. Cleaning up those yards therefore has benefits that reach beyond the pier.

Warships in a warming world

Out at sea, shipping already produces close to 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and some analyses warn that this share could climb toward the high single digits or even around 10% by mid century if traffic keeps growing and fuels do not change fast enough.

International regulators under the International Maritime Organization have started to respond. They adopted a greenhouse gas strategy and a hybrid net-zero framework, and major economies have backed moves toward global pricing of shipping emissions to help pay for cleaner technology and fuels.

The U.S. Navy itself released a Climate Action 2030 plan that promises a climate-ready force, more resilient bases and a faster shift toward low-carbon fuels and hybrid engines for ships and aircraft. Officials have highlighted hybrid propulsion on ships such as USS Makin Island and a net-positive energy Marine Corps base in Georgia as early examples, while acknowledging that much more work lies ahead.

All of that climate ambition, however, collides with GAO’s warning that the shipbuilding system is stuck in the wrong current. Without a course change, the industrial base that needs to deliver cleaner ships and greener yards may be too overloaded just keeping up with late and over budget programs.

The Trump class and the next wave of emissions

From a climate and industrial perspective, the Trump class matters for more than geopolitics. A much larger hull means more steel, more welding, more coatings and more demand for electricity and fuel inside shipyards that already operate near the edge of their capacity. Unless those yards rapidly adopt low-carbon technologies such as cleaner electricity, more efficient equipment and better waste and water systems, each new mega project becomes another source of long-lived emissions.

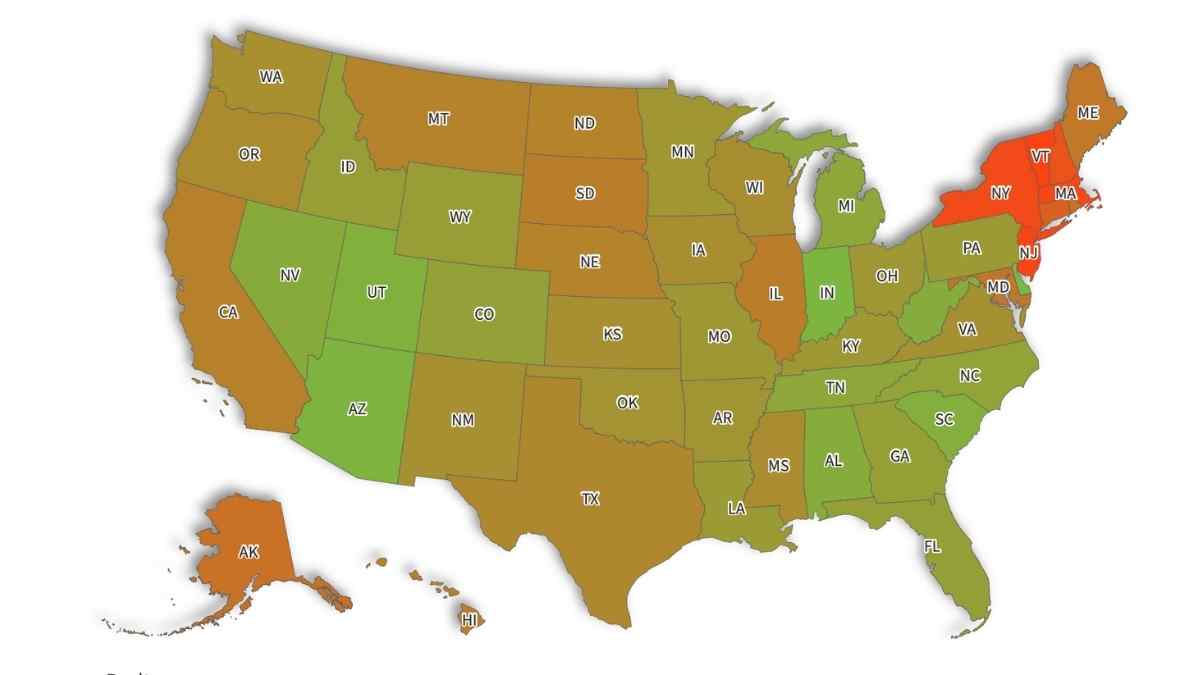

For communities near major shipyards, that is not an abstract concern. It affects the air they breathe, the noise they hear and, in some cases, the health of nearby waterways and fisheries.

An opportunity hiding inside a crisis

The good news is that researchers now have detailed models of how to cut the carbon footprint of shipyards, from zero-emission yard concepts to step-by-step plans that prioritize equipment upgrades, process improvements and fuel switching. Some studies even offer quick methods for estimating the carbon footprint of a ship during the design phase, so environmental performance can influence key decisions rather than becoming an afterthought.

In practical terms that means every dollar the Navy and Congress spend to fix the shipbuilding crisis can either prop up the old way of doing things or accelerate a shift to cleaner steel, smarter yards and more efficient vessels. For people living near shipyards, it could mean the difference between breathing toxic fumes for another generation or seeing heavy industry modernize in ways that respect their health.

At the end of the day, the Navy’s shipbuilding mess is not only a strategic vulnerability. It is also a test of whether a major public institution can align long-term security, industrial policy and climate responsibility while the clock keeps ticking.

The official statement was published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.