Look up at a clear night sky and everything seems calm. Satellites glide silently overhead, keeping your maps app working, your weather alerts accurate, and even helping scientists track melting ice and shrinking forests.

Yet a new study warns that this invisible infrastructure now behaves like a fragile house of cards. One strong solar storm and a brief loss of control could trigger a chain of collisions in low Earth orbit within only a few days.

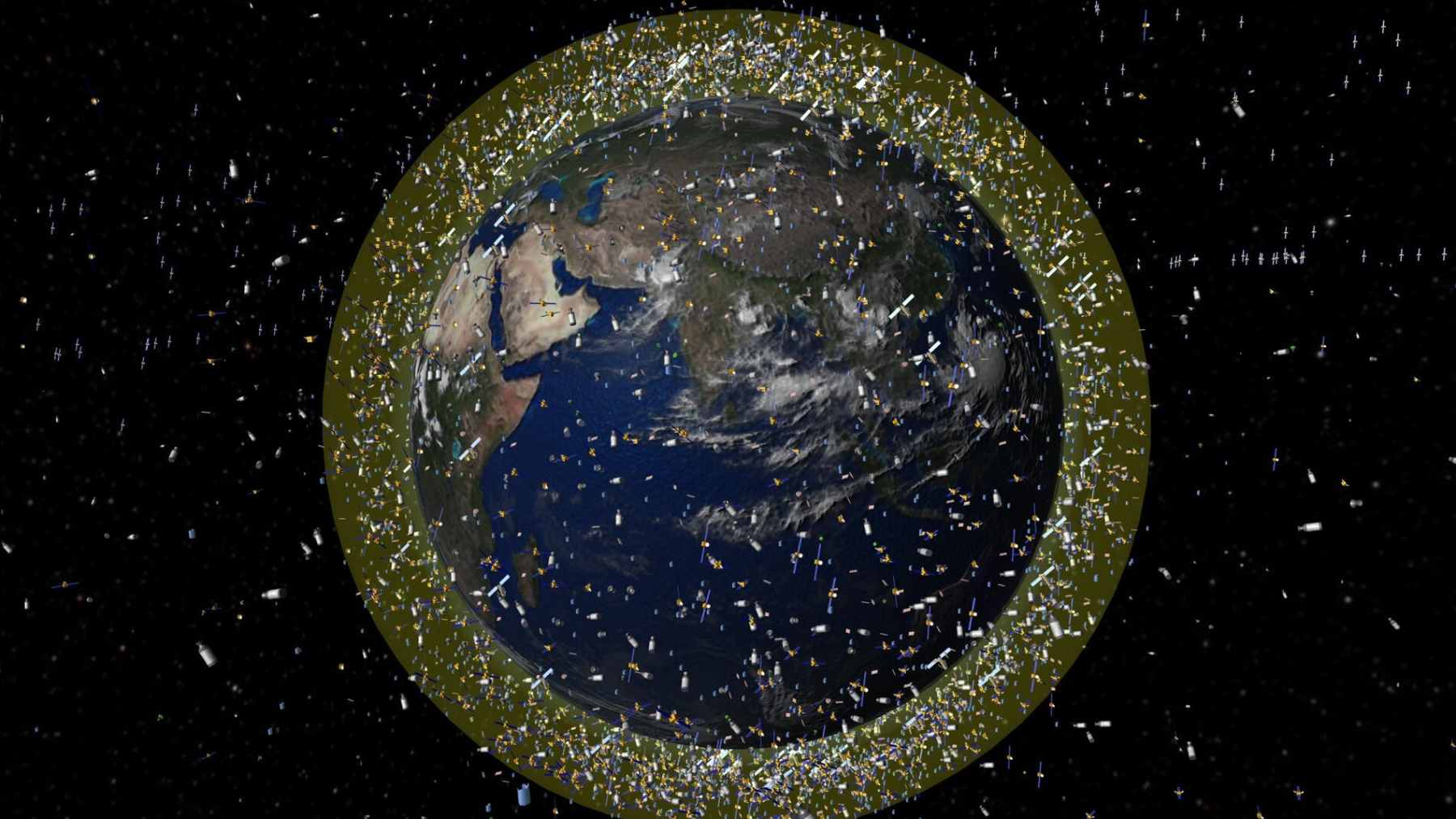

A crowded orbital house of cards

The study, led by astrophysicist Sarah Thiele and colleagues, looks at the exploding population of satellites in low Earth orbit, especially mega constellations such as Starlink. These systems pack thousands of spacecraft into a few narrow orbital shells.

The team finds that close approaches, where two satellites pass within less than one kilometer of each other, already happen at a startling pace. Taken together, all mega constellations experience one of these near passes roughly every 22 seconds. For Starlink alone, the average is about every 11 minutes.

To keep this orbital traffic jam under control, satellites constantly adjust their paths. SpaceX reports that Starlink spacecraft performed more than 140,000 collision avoidance maneuvers over six months, which works out to about 41 maneuvers per satellite each year. In practice, that means somewhere above you a satellite is firing its tiny thrusters every couple of minutes just to keep things safe.

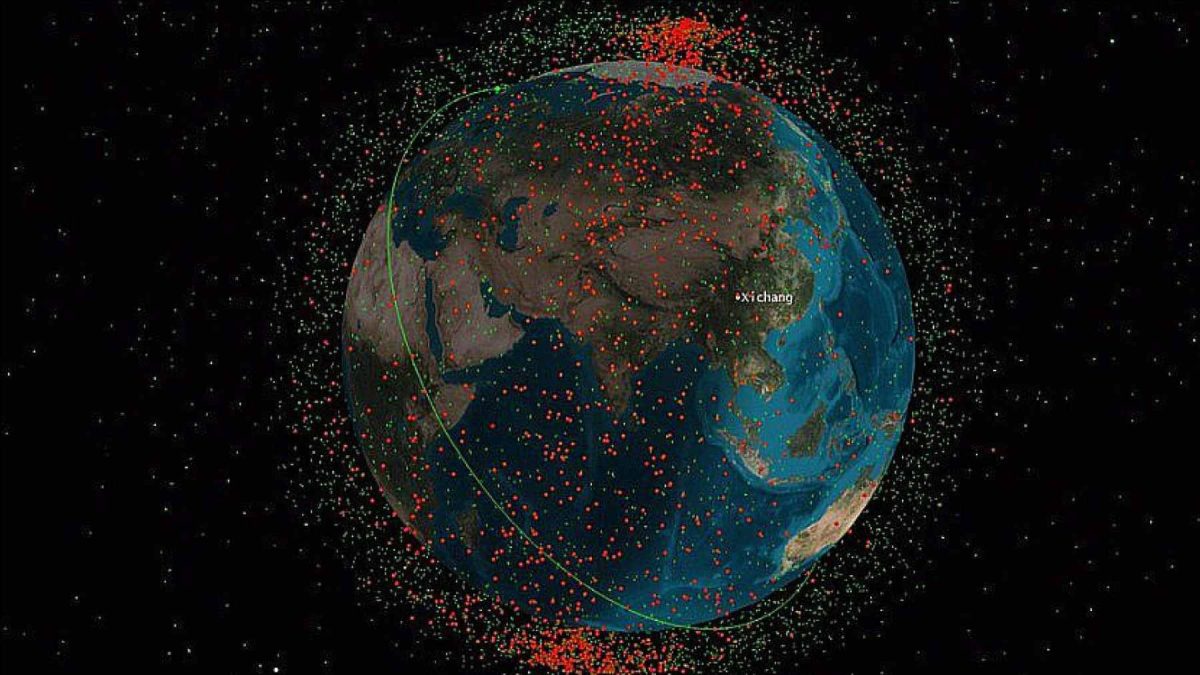

Thiele’s team turns these statistics into a new metric called the CRASH Clock, which estimates how long it would take for a catastrophic collision to occur if satellite operators suddenly lost the ability to maneuver or track objects properly. In the first version of their analysis, the clock read 2.8 days.

A revised version, which adjusts some of the model assumptions, stretches that to about 5.5 days. Either way, the message is the same. The safety margin has shrunk from months to only a handful of days.

When the Sun shakes the system

So what could actually knock out control of so many satellites at once?

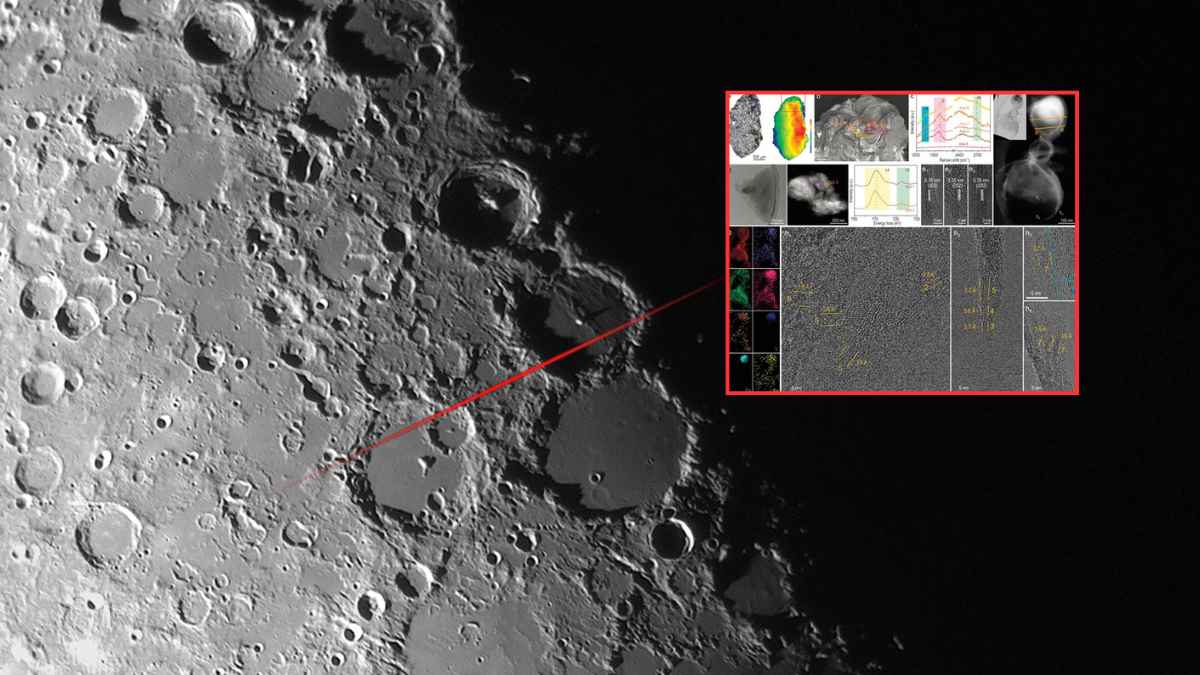

One prime suspect is a major solar storm. When powerful eruptions from the Sun slam into Earth’s magnetic field, they heat and expand the upper atmosphere. That puffed up air increases drag on satellites, making them lose altitude faster and making their future paths harder to predict. A strong storm in May 2024, known as the Gannon geomagnetic storm, was the most intense in more than twenty years and forced many low orbit satellites to perform sudden orbit raising maneuvers all at the same time.

Solar storms can also disrupt onboard electronics, navigation, and communication links. If operators cannot reliably talk to their satellites during such an event, those spacecraft cannot dodge debris or one another.

Combine higher drag, fuzzier tracking data, and momentary loss of control and you have exactly the kind of edge case that worries the authors. In their words, low Earth orbit increasingly behaves like a house of cards, where one unlucky impact can set off further collisions.

From orbital clutter to environmental risk

At first glance, this may sound like a problem for space agencies and telecom firms, not for daily life down on the ground. Yet our environmental awareness now leans heavily on satellites.

Earth observation missions watch wildfires in real time, track illegal deforestation, monitor ocean temperatures, and measure greenhouse gases that drive climate change. Lose those eyes in the sky and the next record heat wave or megafire season becomes much harder to see coming.

The study also points out that mega constellations bring their own environmental footprint. More launches and reentries add pollutants to the upper atmosphere. Bright satellite trails interfere with ground-based astronomy, making it harder to study everything from near Earth asteroids to distant galaxies.

All of this is part of what researchers now call the orbital environment, a shared space that can be degraded much like oceans or the atmosphere.

What can be done?

The CRASH Clock is not a prediction that disaster will strike on a specific date. It is more like a stress test of the orbital system. It asks a simple question. If something big went wrong, how long would we have before the first really bad crash?

Right now, that answer is measured in days, not seasons. Experts suggest that several steps could lengthen that clock.

These include stricter international rules on debris mitigation, higher success rates for end-of-life disposal, better coordination between operators, and satellite designs that reduce collision cross sections and burn up cleanly on reentry. Stronger space weather forecasting and automatic safe modes for satellites during major storms would also help.

For people on the ground, the choices may feel distant, but they are not abstract. The same satellites that help you avoid traffic jams and plan your weekend around a storm front also keep scientists informed about melting glaciers, shifting rainfall patterns, and rising seas. Protecting the orbital environment is part of protecting Earth itself.

The study was published on arXiv.