Most Californians only think about commercial driver’s licenses (CDLs) when a package shows up late, a store shelf is half empty or a moving truck fails to appear.

Behind those small annoyances sits a huge logistics machine powered by more than 130,000 truck drivers working across the state’s freeways, from the Bay Area to the Inland Empire.

Now a federal warning has dropped those drivers into the middle of a fight between Sacramento and Washington. The U.S. Department of Transportation has told California that its commercial driver’s license program may be out of step with federal law.

If the state does not fix the problems, it risks losing federal highway funds and even its authority to issue CDLs that other states recognize.

For drivers, employers and anyone who relies on those trucks, this is not just a technical argument about regulations; it is a fight that could affect jobs, shipping schedules and prices.

Why is California’s CDL program under federal threat?

In an annual review completed this year, federal regulators dug into how California’s Department of Motor Vehicles issues commercial driver’s licenses to noncitizen drivers. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, the agency that oversees commercial trucking safety, concluded that the state had improperly issued thousands of non‑domiciled CDLs.

This is a type of commercial license for people who are allowed to work in the United States but are not permanent residents or citizens of the state that issues the license.

In some cases, license expiration dates stretched years beyond the driver’s lawful presence in the country, even though California law requires those dates to match immigration documents.

As a result, FMCSA sent Governor Gavin Newsom and DMV Director Steve Gordon a conditional determination letter, a formal notice that California has failed to meet specific federal requirements for CDL issuance and must carry out a corrective action plan.

The letter warns that, if the DMV does not show it has implemented that plan, the agency can withhold up to 4% of certain federal‑aid highway funds and move toward decertification of the state’s CDL program.

Under federal rules, decertification means the state can be barred from issuing, renewing, transferring or upgrading commercial licenses until the problems are corrected.

This showdown comes just as California is now canceling about 17,000 commercial licenses that had been issued to noncitizen drivers. Earlier in November, the DMV notified those drivers that their CDLs will be terminated within 60 days because the license expiration dates extend beyond their federal work authorization, something state officials say violates California law.

The governor’s office argues that the drivers originally held valid federal work permits and that state law simply requires DMV records to match those federal dates.

In Washington, Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy has portrayed the mass revocations as proof that California was caught breaking the rules and putting unsafe drivers on the road. Newsom’s team has responded that federal officials are misrepresenting the state’s safety record and turning a licensing dispute into a political fight.

For trucking firms that rely on long‑time employees, the debate over who “lied” to whom matters less than the immediate problem that dozens of experienced drivers per company could soon be sidelined.

How did a Florida crash and new federal CDL rules push this fight nationwide?

This story does not begin in Sacramento but on Florida’s Turnpike. In August, a widely-publicized crash about 50 miles north of West Palm Beach killed three people when a semi‑truck attempted an illegal U‑turn across the highway and a minivan slammed into the trailer.

Federal officials later said the truck driver was in the United States without legal permission and had obtained a California commercial license, kicking off an investigation into how that CDL was issued.

In the months that followed, FMCSA expanded a nationwide audit of non‑domiciled CDLs and, on September 29, issued an emergency interim final rule.

That rule sharply restricts who can receive or renew non‑domiciled commercial licenses, limiting eligibility to noncitizen drivers with specific employment‑based visas such as H‑2A, H‑2B and E‑2, and requiring states to verify immigration status through a federal database and tie license expiration dates to immigration documents or one year, whichever is shorter.

In its own analysis, FMCSA estimates there are about 200,000 non‑domiciled CDL holders nationwide and projects that roughly 194,000 of them would eventually be forced out of the freight market as their licenses come up for renewal under the rule.

However, those new restrictions are not actually being enforced right now. After drivers and unions filed suit in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, the court granted a stay that blocks FMCSA from implementing the interim rule while the case proceeds.

FMCSA has since updated its own public notice to say that, until further notice, states may continue issuing non‑domiciled CDLs under the older standards, except where a state is already under a corrective action plan that pauses certain licenses, as is the case for California.

California’s DMV, for its part, has posted an online notice explaining that it stopped issuing and renewing limited‑term, or non‑domiciled, commercial licenses as of September 29 because of federal emergency rules.

The agency tells affected drivers that if they still have a valid non‑domiciled CDL, no immediate action is required, but those who lose their commercial license can apply for a standard non-commercial license instead. That may keep people driving to work, but it does not solve the basic problem for truckers whose paychecks depend on operating big rigs.

What could happen next if California does not satisfy federal CDL rules?

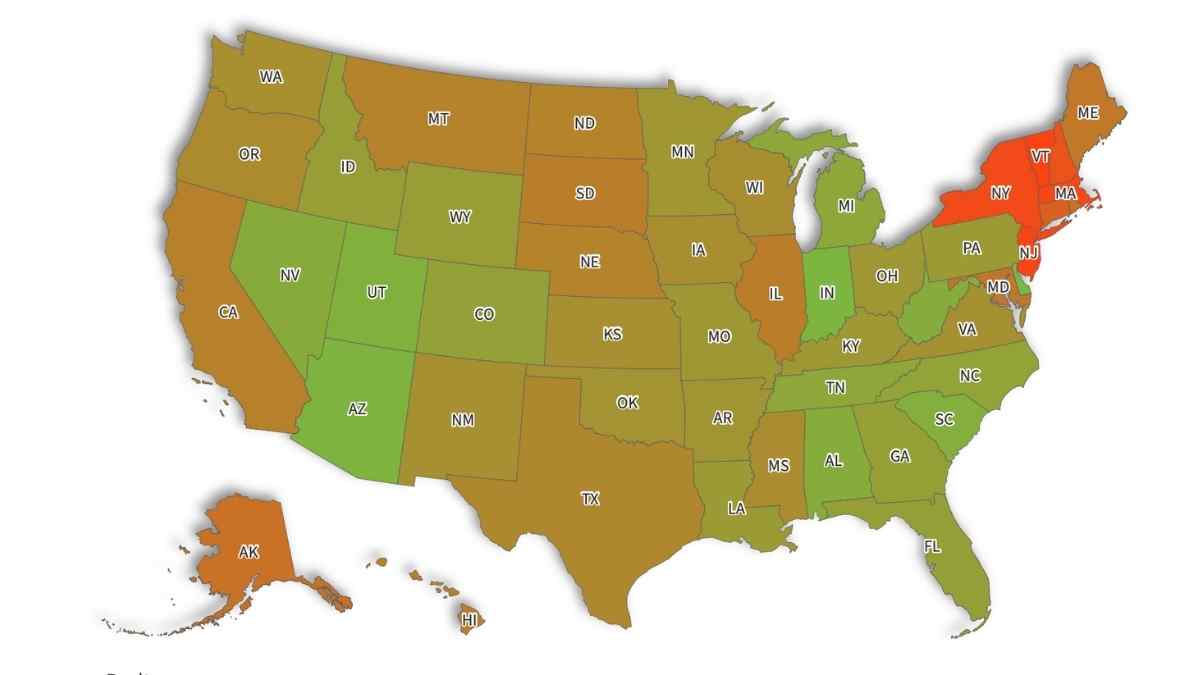

Right now, California is the only state that has received a conditional determination letter on its commercial license program, even though federal audits have found problems in several other states.

Those additional reviews were slowed by the recent record‑long 43-day federal government shutdown, which delayed many inspections and enforcement actions. What happens in California will therefore be watched closely as a preview of how aggressively Washington will push other states once their audits are finalized.

If California convinces FMCSA that it has fully implemented its corrective action plan and revoked or fixed every improperly issued license, the state could avoid both decertification and the immediate loss of highway funds.

If not, the Transportation Department has already threatened to withhold up to $160 million in federal highway money and has previously held back about $40 million over separate disputes about English language requirements in commercial driver testing.

For people stuck in traffic on Interstate 5, those numbers might sound like abstract budget drama. In practice, they could mean fewer road repairs, higher costs for trucking firms that eventually land in consumer prices and more drivers wondering whether their license will still be valid the next time they pull into a weigh station.

The legal and political fight over non‑domiciled CDLs may look technical on paper, but its outcome will shape who is allowed to operate the trucks that keep California’s everyday life running.